Julian of Norwich: The Quiet Voice of Contemplation

By Danièle Cybulskie

When I first started studying the Middle Ages, I had been steeped in the usual simplistic notions of medieval Christianity, believing that there was one form of spiritual practice that varied only slightly; that men were the only ones permitted to think deeply about and guide people’s faith; that people experienced their faith mainly through fear and awe, especially in terms of the terrible torments of hell that awaited sinners. One day, I came across The Shewings of Julian of Norwich, and all my simple ideas of medieval spirituality went out the window.

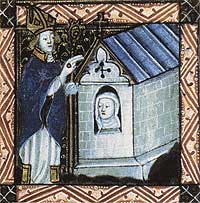

An anchoress, enclosed in her cell.

One might expect that the near-death experiences of a medieval woman as described while enclosed in a stone cell on the side of a church would make them so foreign to a modern person as to be nearly useless; a curiosity, but not much more. Julian’s writing, though, is so alive and moving that it speaks across the centuries, reassuring and comforting, confident and self-assured. Her words are not the words of one who thunders from a pulpit; they are the words of one who takes your hand in your darkest moment and speaks of forgiveness and compassion. It’s no surprise that Julian’s most famous words, spoken to her by Jesus in one of her visions, are in this vein: “al shal be wel, and al shal be wel, and al manner of thing shal be wele” (ll. 938-940). Julian did not condone sin – far from it – but she firmly and fundamentally believed that all could and would be forgiven if only people would ask. Like a mother’s love, Julian believed, God’s love transcended mortal mistakes.

What I love about Julian’s writing is its simplicity, born (I think) of her long-term contemplation. Each chapter of her book is the distillation of decades of thought, pared down into a form that hides the complex thinking behind it. She uses familiar, everyday examples to explain her faith, referring to God’s love, in one example, as “oure clotheing, that for love wrappeth us” (l.146), “For as the body is cladde in the cloth, and the flesh in the skyne, and the bonys in the flesh, and the herte in the bouke, so arn we, soule and body, cladde in the goodnes of God and inclosyd” (ll.210-213). God is not to be simply feared, to Julian’s mind, but to be welcomed and accepted. Sin is also to be accepted as part of God’s plan, for if God has made everything as he wishes it, “How should anything be amysse?” (l.470).

If you’ve come across Julian in the news this month, it’s most likely because TV presenter and historian Dr. Janina Ramirez has just published a helpful and friendly new book on Julian which describes her life and explains her teachings in their historical context: Julian of Norwich: A Very Brief History. While Julian’s writing is remarkable all on its own, you can really get a sense of how she may have been shaped by her circumstances (i.e. the Black Death, the Hundred Years’ War, the ascent of Henry IV) when you look at the bigger picture that Ramirez paints. She discusses how Julian’s approach to faith is strikingly different from, and yet similar to, the writings of other theologians at the time, though (as Ramirez points out) Julian herself would have never considered herself one by any stretch. She recounts the story of Julian’s meeting with the much more public mystic Margery Kempe – one which I have always thought I desperately would have liked to overhear for myself – and how the two women’s experiences compared. Ramirez also speaks to how Julian’s shewings have been received over time, and how they speak to the faithful, or simply the curious, today. In short, Ramirez supplies a lot of the historical details that Julian shies away from.

Ramirez’ book is a great, very readable introduction to Julian that gets at the heart of why her writing is both inspirational to many (both Christian and non-Christian) and historically fascinating. If you’d like to know more about Julian (or anchoresses, or medieval Christianity) I’d definitely recommend that you start there. If your Middle English is pretty good, you can then go straight to The Shewings of Julian of Norwich (the TEAMS edition is great) and dive in. However you encounter Julian, whether for the first time or the hundredth, no doubt you will hear the quiet voice of a lifetime of contemplation, as rich and real as it was hundreds of years ago.