Faith, Art & the People's Well-Being

in an Organic Christian Civilization

Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

Catholic writer Antero de Figueiredo (1866-1953)

If Antero de Figueiredo had done for the cause of the

Revolution - and especially for the cause of Communism - all the good he

did for the Church, today he would be a famous writer in Brazil. All

the outlets of the Left that fabricate popularity, so numerous and

productive, would often praise the unique beauty of his style, his

verve, his profound, pensive and clear thought, as well as his keen

sense of observation.

And numerous Catholic critics from professors’ chairs and the press' desks would emphatically exclaim, "Regarding this great and immortal writer, although I do not exactly share his ideas, I am glad to recognize and proclaim with the most uncompromising impartiality that he had these extraordinary qualities…”

And they would go on to declaim a litany of eulogies copied with humility and precision from the texts of the subversive propaganda.

But, it happens that Antero was Catholic and, an even more serious crime, a genuine Catholic, a fearless and efficient apostle of the Counter-Revolution.

This is why his name has fallen into oblivion. It is because this same inferiority complex – fomented by the lack of faith, tepidity and coquetry that induces us to be incense-burners of the Revolution – robs us of the necessary brio to affirm the values of a true culture, a truly Catholic culture.

We transcribe, then, a passage of Antero in which he extols one of the most beautiful aspects of what a people is in a Christian Civilization.

Quite the opposite of the anonymous, empty, tired and revolted masses of the proletarian neighborhoods in the big modern cities is that Hispanic people of the Vascongadas (1), ardent in their faith and overflowing with personality and health.

The sons of Guipuzcoa – part of the Vascongadas – all repute themselves hidalgos [noblemen], even the simple small farmers ... with no need for SUPRA (2) or agrarian reform. And Antero de Figueiredo tell us why this is so.

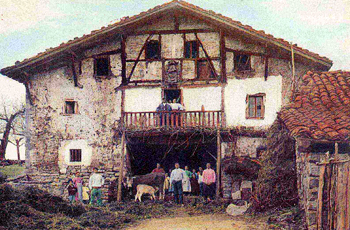

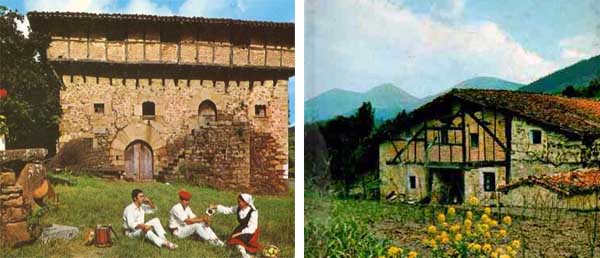

Our pictures, which show houses of Biscaia – also an integral part of the Vascongadas – adequately illustrate the descriptions of the Portuguese writer. Descriptions that provide an excellent set of observations on the organic society that flourished in Spain, our most noble and most Catholic sister.

"Nestled in these green hills (of Guipuzcoa) is the typical Basque house of small famers, a house both rustic and manorial. It is simple in its village lines, noble in its gravity, and picturesque in its ensemble. ...

Two typical Basque houses

"It is always a large house with solid walls, where one finds in a single edifice that which in other lands are separated into distinct buildings: the house of the family, that of the servant, the livestock pens, the haystacks, the workrooms and sheds for plows, harrows and all the agricultural tools. Under the same roof, the Basque installs the family, servants, livestock, hay, wine cellar, olive drying room and granary. On these houses, the enormous double-sloping tile roof ... expresses the patriarchal life where the men, women, children, animals, utensils, tools are all housed together and sheltered under its protection.

"On its façade, the eaves collaborate aesthetically to provide shade, materially to provide comfort and, morally to offer a warm gesture of shelter. How honorable and affectionate those roofs and eaves are! One has the impression that, in the long winter evenings, at the blessed hour of reading from the holy books and common prayer, all the people and things – the family, servants, plows, distaff, plate of bread, cider vats, olive oil jugs – all accompany the prayers of the lord and master. It seems as if the livestock in their pens maintain a religious silence and the souls of brute beasts and household objects are Christianized, hearing the words of Jesus. …

"To reach the first floor one climbs an outdoor stone stairway with a veranda at the entrance – a veranda that gives one the foretaste of a religious and hospitable welcome. The architect, thinking first of the usefulness of the building, thought less perhaps of beauty in its construction; notwithstanding, beauty flowered there spontaneously, born logically from the architectural arrangement, with ornaments so natural that his art is the best, because it is an art that does not view itself properly as such.

"To better support the clay and limestone filling of the walls, the beams must be close to each other and jut out; painted green, their vertical and equidistant lines adorn the façade. The rough finish of the yellowish limestone of the arch and thresholds of doors to the veranda fits the ensemble so well that one might think it was made in a rustic Florentine style. And, on the overhead corner, the large and small interlocking stone spires, set in open relief, burned by the sun and grown musty by time, adorn the façade with their colorful fissures that stand out in the limestone.

"The exterior walls of the house are filled with color – light and shadow – from the crests to the dark tiers of rafters that support the large veranda. It is made more colorful by the grapevines that fall over the parapet with wreaths of green tendrils linking the house to the green fields and the tops of the trees.

"And none of these families of small farmers would fail to display symbols of their religious faith and their heraldic shields. Embedded on the walls are bas-reliefs of patron saints who protect the household alongside coats of arms in this region where the majority considered themselves hidalgos, because, according to the Basque writer Perochegui, "Vascongadas and Navarre are the seminaries of the nobility of Spain."

"Sancho VIII the Strong, protector of the villagers of Navarre, made everyone noblemen because, as he said, ‘All are equally noble, because their nobility has a single origin.’”

The Basque casario in the countryside can be elaborate or simple,

but it is always charming and picturesque

- Vascongadas, also Bascongadas, is in Spanish, literally, the Basque-speaking provinces.

- State supervisors of Agrarian Policy created during the Goulart government that was mandated to implement Socialism

- Anton de Figueredo, Espanha, 4th ed, pp. 280-285

Related: