Monarch Profile: King Sigismund III of Poland

MadMonarchist

The reign of King Sigismund III of Poland is often spoken of as the beginning of the end of Polish greatness. In terms of worldly success he certainly met with many defeats and setbacks. Yet, he was also one of the great Catholic champions of Europe and his reign can also be seen as one of many opportunities for an even greater Poland had things gone just a little differently. He was also a man of principle who would follow the hard but upright path rather than compromise his values for a more sure chance at success. As a monarch who reigned during the Catholic Reformation (also called the counterreformation) he constantly worked to see the restoration of all of his subjects to the true faith embodied in the Church of Rome. Oddly enough for such a staunchly Catholic monarch his story begins in the staunchly Protestant Kingdom of Sweden.

Sigismund was born on June 20, 1566 to Katarzyna (Catherine) Jagiellonka

and King John III of Sweden at Gripsholm. His parents, at the time,

were being held prisoner by King Eric XIV but despite the Protestant

domination of Sweden young Sigismund was raised as a Catholic. Regaining

the throne of Sweden would be one of the primary driving forces in his

life. His Polish connection came through his mother who was the daughter

of Sigismund the Old and the Jagiellonka family had been the royal

family of the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth since King Wladyslaw II

obtained the crown in 1386 through his Angevin wife. In 1587 Sigismund

stood for election to the Polish throne after the death of King Stefan

Batory. He was supported by Chancellor Jan Zamoyski, the dowager Queen

Anna and the nobles loyal to the Zborowski family. With this network

behind him he was duly elected King of the Polish Lithuanian

Commonwealth on August 19, 1587 with the blessings of the primate of

Poland Stanislaw Karnkowski. From that time his official name and title

became Sigismund III, by the grace of God, king of Poland, grand duke of

Lithuania, Ruthenia, Prussia, Masovia, Samogitia, Livonia and also

hereditary king of the Swedes, Goths and Wends; the later titles being

in reference to the claims of his father to the Swedish throne.

However, as was often the case with the Polish electoral monarchy, the

outcome was strongly contested by the losers who backed the Emperor

Maximilian III for King of Poland. Upon hearing of his election King

Sigismund slipped through the clutches of the Protestants in Sweden and

landed in Poland on October 7 and quickly agreed to give up some royal

powers to the parliament of the commonwealth in the hope of wining over

some of his enemies and settling the disputed election. He was

proclaimed by the Lesser Prussian Treasurer Jan Dulski as king on behalf

of the Crown Marshal Andrzej Opalinski and after journeying to Krakow

he was crowned on December 27. It would have seemed that the issue of

who would be King of Poland had been settled by Emperor Maximilian III

invaded at the head of his army to claim his crown. Thankfully,

hostilities did not last too long as hetman Jan Zamojski at the head of a

Polish army loyal to King Sigismund met and defeated the Austrians at

the battle of Byczyna and took Maximilian III prisoner. However, at the

request of Pope Sixtus V, King Sigismund III released Maximilian who

surrendered his claim to the Polish commonwealth in 1589. King Sigismund

also tried to maintain peace with his powerful neighbor by marrying

Archduchess Anna of Austria in 1592. His was always his intention to be

allied with Catholic Austria against the Protestant forces that were

tearing Christendom apart.

When his father died King Sigismund III requested from his parliament that he be allowed to claim his inheritance as the rightful King of Sweden. The Poles had no objection and when he promised to respect Lutheranism as the official religion of Sweden the Swedes went along with the idea as well and Sigismund was crowned King of Sweden in 1594. He appointed his uncle, Duke Charles, to rule as regent on his behalf in Sweden while he remained in Poland since the Swedes and the Commonwealth were not united politically but simply had a personal union by sharing one monarch. However, tensions grew quickly with Sweden as despite the legal guarantees, King Sigismund was a devout Catholic and this made the Swedes nervous. The Protestant firebrands warned that Sigismund had the ultimate goal of making Sweden Catholic again. As proof they pointed to the Union of Brest Sigismund set up in 1596 which brought many Eastern Orthodox into the Catholic fold and led to the modern day Ukrainian Catholic Church, to his friendship with Catholic Austria and his support for the Catholic Reformation, particularly the Jesuit order, which was spreading out to refute Protestantism and regain lost spiritual ground for Rome.

Combating heresy and giving Poland, long a politically chaotic country, a

strong and stable government were the primary goals of King Sigismund.

Toward this end he moved the royal palace from Krakow to Warsaw and

oversaw the arrival of the Jesuits who set up many schools throughout

Poland and became chaplains and confessors to many families. The

Catholic Church in Poland rebounded strongly during the early years of

the reign of King Sigismund III. Their preaching was very well received

by the public and along with their staunch defense of the faith they

also reminded Poles of their crucial role as the first line of defense

for Catholic Christendom against the Russians and the Turks. However,

trouble was never far away for King Sigismund and 1598 was a

particularly painful year. His wife Anna died (he later married her

sister Constance of Austria in 1605) and he saw the outbreak of

rebellion in Sweden led by his own uncle and regent who portrayed

himself as the Protestant champion of Sweden fighting against their

Polish Catholic monarch. King Sigismund moved against him which a

combined Swedish and Polish army. He won some early victories but the

climax came at the battle of Stangebro in which his 8,000 strong army

was defeated by the 12,000 men of Duke Charles. The Swedish loyalists

were executed by the Protestant government and after the King returned

to Poland he was declared deposed and his uncle was proclaimed King

Charles IX of Sweden in 1600. A number of Swedish Polish wars resulted

but the personal union was never to be recovered despite the many

persistent efforts of King Sigismund.

Trouble was also plentiful on the southern border where Poland was drawn

into the wars of local nobles and the Austrian Hapsburgs against the

Muslim Tartars and Turks. King Sigismund was anxious to help Austria and

was promised territorial gains for Poland in return for his assistance.

He sent in a mercenary army fresh from the wars in Russia to Moldavia

but in 1620 the Polish forces were defeated and Sigismund was forced to

renounce his claim to the principality. It was a setback but resulted in

a negotiated peace and was no stunning victory for the Muslims who had

vowed to destroy the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth and in this aim they

certainly failed. Almost at the same time as these troubles, and those

with Sweden, Sigismund was fighting a war with Russia. Those who

remember the World War II era of Polish wars against Germany and Russia

should set any preconceptions aside because in the time of the

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth it was the Poles that were a force to be

reckoned with, especially their elite heavy, winged, hussars. The

Russians had been fighting amongst themselves and King Sigismund got

involved, as did Sweden though they were never firmly on one side or the

other. At one point the Russians invited the son of King Sigismund to

become their Tsar but Sigismund would not allow it. He though he himself

might become the master of Russia and though this did not happen the

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth did win a number of victories and gained

more territory. At one point Polish troops even captured Moscow as

astounding as that might seem today. On the downside the whole conflict

meant that any lasting union between the Commonwealth and Russia was out

of the question.

Throughout all of these constant wars King Sigismund also tried to

stabilize and streamline the Commonwealth government. The electoral

monarchy in Poland had created a nobility with rather too extensive

powers and a great deal of division. Sigismund worked to gain more power

for the king as well as to allow government business to pass with a

majority of votes of the parliament rather than unanimity which was

extremely hard to achieve and men that things often did not get done.

All these actions led to a rebellion but the King was ultimately

victorious and despite what his many detractors might say his reign

marked a period of Polish greatness the likes of which has not often

been seen. He made the Commonwealth very much the dominant power of

Eastern Europe and just as importantly ensured that Poland remained a

solidly Catholic country in the face of Protestant incursions. He was a

brave man, a talented monarch and something of a renaissance man as is

evidenced by his devout faith and his artistic talent as a painter and

goldsmith. Had things gone just a little bit different he might have

been the father of a Catholic dynasty that stretched across Sweden,

Poland-Lithuania, Moldavia and Russia. It did not happen, but that

should not detract from his greatness as one of the royal champions of

the Catholic Reformation period. King Sigismund III died on April 30,

1632 at the age of 65 in his castle at Warsaw and was succeeded by his

son King Wladyslaw IV.

Related:

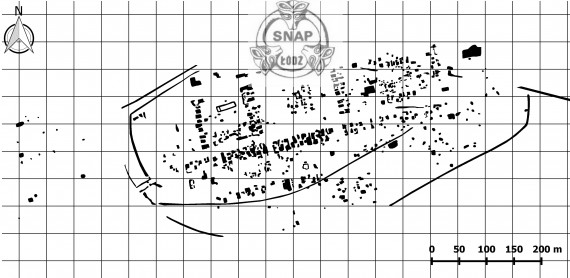

Discovering a Lost Medieval Town in Poland

A

three-dimensional, artistic digital reconstruction of New

Nieszawa/Dybow on the basis of non-invasive data (by J. Zakrzewski, S.

Rzeznik, P. Wroniecki)

By Marcin Jaworski and Piotr Wroniecki

The 15th century city of Nieszawa, known by two names Nowa Nieszawa (New Nieszawa) or Dybów was a prosperous urban centre on the border of the Polish Kingdom and the Teutonic Order. In nearly 40 years of its existence the city became the main rival of the Order’s city of Torun (Thorn), a member of the Hanseatic League. The circumstances of the town’s founding as well as destruction and translocation to the place where it is located today were inseparably connected with the history of Polish-Teutonic struggle for domination in the region and profit from trade in the middle and upper course of the Vistula river – an important trade route connecting the Poland with the Baltic Sea. Nieszawa was deliberately located opposite to Teutonic Torun in order to become an economic and political weapon in this conflict. Nowa Nieszawa’s dynamic development could not be stopped neither by Teutonic Order’s political demands, neither by its armed assaults, yet the city’s successful competition was in the end awarded by destruction and translocation. Due to very fortunate coincidences the relicts of the city remained largely undisturbed for five and half centuries until modern archaeological techniques enabled to conduct non-invasive archaeological surveys which brought it back on the maps of medieval history.The history of the first location of Medieval Nieszawa

It is believed that in 1423 AD by the will of Polish King and Lithuanian Grand Duke Wladysław Jagiełło a village called Nieszawa was located on the western bank of the Vistula river, opposite to Teutonic Torun. Not later than in the beginning of the year 1424 the King granted town rights to the settlement. Nowa Nieszawa developed very rapidly, benefitting from its profitable location on the Vistula, near the border crossing through the from the rich Kuyavia region of Poland, through the Teutonic lands to the shore of the Baltic Sea. Its buildings were mainly raised in timber or wattle and daub construction, but the municipal and religious structures (like the town hall or churches) were built in brick. In the vicinity of the city to the east the Polish king built a brick castle called the Dybów Castle in between the years 1427-1430.

The development of the city was stopped when a successful raid in 1431 by Teutonic knights and the townspeople of Torun destroyed it and put the area under Order’s jurisdiction for the next years. The overtaken Dybów castle became the temporary seat of the Teutonic state’s administrative unit (called a commandry) formed on the occupied lands on the western bank of Vistula. The area opposite to Torun, together with the lands in Kuyavia and the Dybowski castle returned to Poland after the treaty signed in 1436. It marked the reconstruction of Nieszawa and a new period of rapid development. Its basis consisted again of the far-reaching trade of goods such as grain, fish, oil and beer. Economic rivalry on the Vistula resulted in numerous conflicts with merchants from Teutonic Prussia. In the same period, the citizenship in Nieszawa was granted to refugees from the oppressive state, and what is most interesting their social status was irrelevant as they originated from various layers of social stratum (knighthood, townsfolk or peasantry), which is testified by historical documents. Nieszawa was also a home for a multicultural society consisting of Poles, Germans, English, Czech, Dutch and a Jewish community.

Aerial

photography revealing details of constructions in the western part of

the studied area with a clearly emerging frontage and a centrally

located object, June 2012 (by W. Stępien)

Fifteen years of research

The memory of the thriving city faded. Its original area was partially destroyed and transformed in time through regulation of Vistula’s course, construction of anti-flood embankments and development of modern urban infrastructure. The interest in the past urban organism was raised during archaeological fieldwork at the Dybow castle commissioned to Lidia Grzeszkiewicz-Kotlewska by Torun’s Heritage Office. Fieldwork in the surroundings of the castle started in 1990 through application of a GPR, followed in consequent seasons by test trenching. By 2002 a number of 32 trenches have been documented, revealing a cultural layer dated to 15th c, including relicts of building in wooden and brick construction. Aerial survey of the fields west to the castle started in 2001 as documentation of the excavations, but turned into a consequent annual observation and documentation of the vast area. In 2006, through the application of aerial archaeology, it was possible to register visible crop marks, forming regular patterns of rectangular shapes. Their recurrence in following years allowed to assume that there might be a system of archaeological structures present in the subsoil.

This initial archaeological and aerial survey motivated a large scale, complex non-invasive survey with the application of geophysical methods. The fieldwork in 2012-2014 consisted of magnetic, earth resistance and magnetic susceptibility measurements that covered the overall area of almost 50 hectares. The survey registered geophysical anomalies that testified to the existence of remains of a vast urban organism with a clearly organised spatial pattern. Integration and juxtaposition of the obtained data, together with the results of previous studies resulted in recreation of the spatial layout of the city and creation of digital 3D models reconstructing the hypothetical shape of the city.

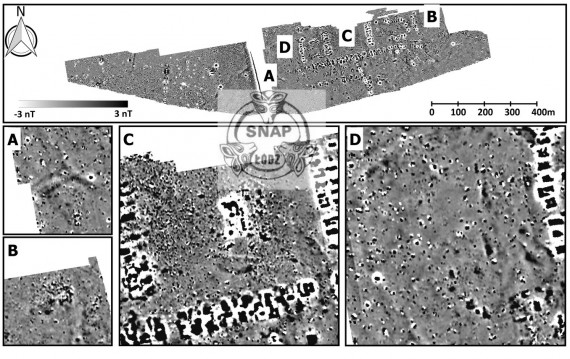

Detailed

results of magnetic gradiometry prospection. A) Possible western gate

with bridge, B) Remnants of the St. Nicholas Church, C) Town Square, D)

Western town district (P. Wroniecki)

Nowa Nieszawa was a vibrant merchant city, inhabited by a few thousand people from all around the Polish Kingdom and contemporary European states. It possessed a dense architectural structure, an enormous town square, carefully plotted blocks of urban plots with space for religious and municipal buildings, commercial areas and storage buildings for trade goods (i.e. the granaries for grain). Past years of archaeological research resulted in the conclusion that the effort put in location and development of Nowa Nieszawa was an extensive economical and political strategy aimed against the Teutonic Order and its plans for domination in the river trade and region.

Past fifteen years of experience

A summary of past fifteen years of experience has been published in a form of a monograph publication called “In search for the lost city: 15 years of research of Medieval location of Nieszawa”. The book is published by the Lodz city branch of Scientific Association of Polish Archaeologists (SNAP Lodz) and The Institute of Archaeology of Lodz University as a collective work consisting of theme papers prepared by the circle of scholars involved in the research on the course of past one and half decade. The book consists of an elaboration of historic sources concerning the city, followed by reports on various stages of field exploration. A geomorphological report studies the natural conditions present at the site. Aerial survey conducted in the years 2001-2014 is summarised and illustrated by numerous pictures of the site in annually changing conditions. A summary of all seasons of excavations is accompanied by archive photographic documentation and drawings of artefacts. Results of geophysical survey with application of magnetic, Earth resistance and magnetic susceptibility measurements are aided by illustrations of the results and their interpretation. The text is filled with digital three-dimensional artistic reconstructions of the city. The current state of knowledge is summarised in an urban analysis based on historic, archaeological and non-invasive data. Although published and intended for the Polish scientific community the publication contains also a summary in English.

A three-dimensional, artistic digital reconstruction of New Nieszawa, view from the Vistula (by J. Zakrzewski, T. Mełnicki).

The publication of the monograph was co-financed by the Polish Ministry of Culture and National Heritage. The book is soon to be published online on the project’s site: staranieszawa.pl.

You can also watch a digital reconstruction of the city in a movie called “Nieszawa: a forgotten medieval city in Poland discovered with the use of remote sensing techniques” posted on YouTube: