Currency Wars: The Race to the Bottom Has Begun

If trade wars and actual shooting wars (Syria, Yemen)

weren’t enough for the world economy to worry about, pressuring stock

markets and threatening to derail robust global economic growth, there

is another elephant in the room looking to stomp on traders, investors

and everyday consumers, and that is a currency war.

What is a currency war?

A

currency war is what happens when countries intentionally devalue their

currencies through their central banks. Increasing the money supply

lowers interest rates and the value of the currency, thereby depressing

the exchange rate. The best example of this type of expansionary

monetary policy is that of the United States Federal Reserve. The Fed

buys Treasury notes from its member banks, giving them more money to

lend. To do this, the Fed must print more US dollars. The idea is to

stimulate demand by reducing lending rates and therefore entice

businesses and individuals to borrow and spend more money. Until last

September, when the Fed wound up its last round of quantitative easing,

this policy led to rock-bottom interest rates and has been behind the

record-setting highs hit on US stock markets. Low interest rates mean

companies can borrow, expand and grow, thus boosting profits and share

prices.

In

a currency war, those on the losing end of trading relationships decide

to engage in a policy of competitive devaluation. By keeping their

currencies low, through monetary policy explained above, the idea is

that exports will be cheaper. On the other hand, devaluing a currency

also makes imports more expensive, which can hurt companies that

purchase a lot of foreign parts for assembling their products.

The

term “currency war” was first coined by Guido Mantega, the former

finance minister of Brazil, in 2010. Mantega was describing the

competition between the US and China to have the lowest currency value,

ergo the cheapest exports, which hurt Brazil because it meant that low

interest rates implemented in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis

caused investors to pour cash into Brazil, which had much higher bond

yields. This made commodities that Brazil exported more expensive,

because commodity prices rise when the dollar falls.

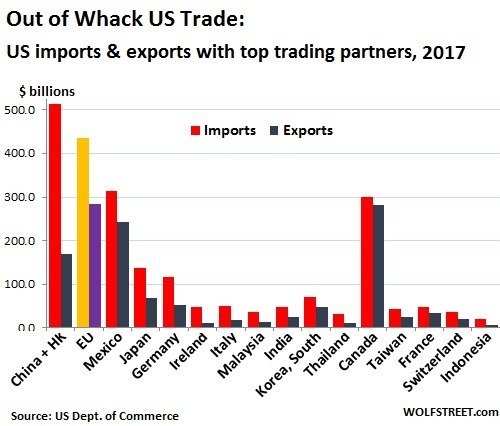

The

problem for the United States is that throughout the past several

years, the dollar has remained high in relation to other currencies, and

that has created a large trade deficit – at last count $566 billion for

2017. It’s a problem because a trade deficit means the US imports more

than it exports – meaning consumers are buying more goods and services

from abroad than locally. Exporters face resistance from buyers because

products priced in dollars are more expensive.

It

is primarily the result of the trade deficit – and especially the trade

deficit with China, $337 billion in 2017 – that has prompted the Trump

Administration to engage in a series of tariff threats with its most powerful economic competitor.

This

article will show that not only is Trump engaging in a trade war, but

also a currency war with China. Plus a bit of a history of currency

wars. What does a currency war, and a low dollar, mean for investors and

for commodities?

Trump and a currency war

Trump

campaigned on reducing the deficit by hammering US trading partners and

promising to rip up “horrible trade deals” previous administrations had

negotiated. This included NAFTA, the Trans Pacific Partnership which

the US withdrew from, and the trading relationship with China which

Trump has always described as unfair. Trump and other US officials have

accused not only China but Germany, Russia and Japan as trying to gain a

trade advantage by keeping their currencies weak. But Trump has been

doing the same thing. Over the last year the US dollar index (the dollar

against a basket of other trading partner currencies) has dropped

11.4%.

On Monday the President repeated his complaints about competitive currency devaluations from China and Russia, just as the US is raising interest rates – which will put upward pressure on the dollar. “Not acceptable,” Trump tweeted.

Bloomberg

notes that China is indeed considering re-evaluating where it wants the

level of the yuan to be, as it also weighs retaliatory measures on the

United States which has threatened a total of $150 billion worth of

tariffs, not including 10% tariffs on aluminum and 25% on steel

indirectly aimed at China’s steel industry which produces most of the

world’s steel. But it also points out that the yuan has gained 10%

against the dollar over the past year, in March to the strongest level

since August 2015. So much for the yuan undercutting the dollar.

Yuan rise against dollar

The

publication states the latest Trump missive is evidence that the

President plans to engage China, Russia and likely other trading

partners in a war over exchange rates, with the goal being a weak

dollar. His Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said as much earlier this

year when Mnuchin stated that a weaker dollar in the short term benefits

the economy.

[Trump's comments are] “another

implicit signal of the administration’s desire for a weaker U.S. dollar

— especially against major trading partners. These weak dollar

expectations will remain entrenched in currency markets, especially if

the administration continues its mercantilist [maximize trade] policy

focus.” Viraj Patel, a London-based currency strategist at ING Groep NV

It’s

clear that a low dollar is part of Trump’s plan to bring jobs back to

the US after many were exported abroad to take advantage of lower labor

costs, and therefore rebuild the US manufacturing sector, primarily,

through cheaper exports. Quoting Trump:

“You

look at what China is doing to our country in terms of making our

product. They’re devaluing their currency, and there’s nobody in our

government to fight them… they’re using our country as a piggy bank to

rebuild China, and many other countries are doing the same thing.”

“Our

country’s in deep trouble. We don’t know what we’re doing when it comes

to devaluations and all of these countries all over the world,

especially China. They’re the best, the best ever at it. What they’re

doing to us is a very, very sad thing.”

Currency wars: A brief history

You

don’t have to be an economic historian to know that currency wars are

nothing new. Previous presidents have intentionally depressed the

dollar’s value to increase trade, and in fact the idea goes as far back

as the Roman Empire.

When

the Romans gobbled up Egypt, Judea, Britain and Gaul, the Empire became

stretched, with long supply lines requiring more money to maintain. The

drain on gold and silver meant the Treasury could no longer meet its

expenses with revenues, so Emperor Nero decided the only way to bridge

the shortfall was to print more money (sound familiar?). He did this by

reducing the amount of silver in the coins. This soon caught on with

later Emperors, who during the next two centuries cut the amount of

silver in coins from 96% to 0%. The printing of too many coins led to

inflation and a trade deficit with its provinces, as explained nicely by Stephen Pope in Forbes.

Trump

may seems like an outlier economic nationalist with his “Make America

Great Again” slogan and promises to be more protectionist, but previous presidents have sung the same tune. Examples

include all candidates in the 2016 Presidential election criticizing

the TPP; Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton denouncing NAFTA in 2008 –

threatening like Trump to renegotiate the treaty; and Ross Perot back in

1992 with his description of “the great sucking sound” of jobs

disappearing to Mexico.

The

first modern-day instances of currency wars occurred in the 1930s when

countries decoupled their currencies from the gold standard. After the

Great Crash of 1929 there was rampant unemployment throughout the

developed world. When Germany devalued its currency in 1931, Britain –

then the leading industrial power – was hard hit by having its foreign

exchange reserves drained by speculators. The Brits thus decided to end

the attachment of sterling to gold. Countries with ties to the British

Commonwealth quickly exited the gold standard as well – leaving

currencies to float on their own. The

first modern-day instances of currency wars occurred in the 1930s when

countries decoupled their currencies from the gold standard.

Free from a gold peg, these countries found that devaluing their currencies would boost their economies,

a policy that became known as “beggar thy neighbour” because they could

literally export unemployment to another higher-value currency country,

just as China has done to the US.

Interestingly, Market Realist notes that this “go it your own” system destroyed any reason for countries to cooperate in financial matters and may have contributed to the Second World War:

The

combination of the U.K split with gold and a U.S devaluation against

gold that occurred in 1933 promoted the intended currency war tactic.

Both economies’ competitive devaluations prevented prices from falling,

allowed money supplies to increase and bolstered production. The

division between states created a chasm in cooperation. While this lack

of international unity was not the sole catalyst to the destruction of

peace that brought World War II, it was a part of a growing rivalry that

would eventually experience real war. - Market Realist

The

Bretton Woods Agreement of 1944 set up an international economic system

resting on both gold and the US dollar. The signatories included all

the major industrial powers including the US, Japan, Canada, Australia

and Western Europe. The system worked well for about 30 years but in

1973 US President Nixon took the US off the gold standard. Other

countries followed and currencies were again allowed to float against

one another. But the US was clearly the most powerful currency,

especially following an arrangement with Saudi Arabia in the early 70s

to sell Saudi oil in US dollars in exchange for US military protection.

This

post-Bretton Woods arrangement worked until 1999 when the European

Union set up a monetary union with a single currency, the euro. This

ended competition between European countries and instead set up a

showdown between the dollar and the euro for currency dominance.

Unexpectedly

however, the threat came from Asia, not Europe, in the mid-1990s. The

collapse of Thailand’s currency, the baht, in 1997 caused a contagion of

devaluations throughout the region. Members of the ASEAN block were

unable to pay their debts, forcing a bailout from the IMF. But as a

condition of the bailouts, the countries were required to make regular

debt repayments and to have a greater amount of foreign reserves. This

created a new demand for the US dollar, the most powerful currency.

Fast

forward to 2008, the financial crisis. With global growth in the tank, a

new currency war was about to break out, with most developed countries

seeing increased exports as the way out of the low growth dilemma.

Countries began lowering interest rates to encourage borrowing and

consumer spending, which also dropped currency valuations.

“In

its latest effort to try and stimulate the U.S. economy, the Federal

Reserve cut its key interest rate to a range of between zero percent and

0.25%, and said it expects to keep rates near that unprecedented low

level for some time to come.” CNNMoney.com,December 16, 2008

Money

started flowing to emerging economies out of developed economies, which

offered higher bond yields such as the situation with Brazil described

above.

One exception was Japan, which saw the yen lose about a third of its value between 2012 and 2014, meaning higher profits for exporters like Toyota.

Dollar Yen Exchange Rate

The

Japanese took their success one step further, in 2016, lowering

interest rates below zero in order to further stimulate their economy,

through bond buying similar to what the Fed did during its quantitative

easing rounds. The European Central Bank did the same thing in 2014.

An

important milestone in currency war history was China’s devaluation of

the yuan in 2015. Cutting its rate by 1.9%, the biggest rate drop since

1994, caused a lot of pushback from the US and China’s other trading

partners. This however didn’t stop the yuan from being allowed into the

International Monetary Fund’s Special Drawing Rights in 2016, which are

supplementary foreign exchange assets controlled by the IMF.

Who benefits? Who loses?

There

is a lot of debate about who are the winners and losers of a currency

war. Intuitively the winner is the lowest currency but in reality the

war is a race to the bottom where everybody loses. While exporters may

receive a bump, higher import costs also hurt businesses dependent on

foreign inputs, while consumers face higher prices ranging from food to

gasoline to patio furniture from Walmart. The most pertinent question

right now is, can the US win a currency war? The opinions are mixed.

On

the loser end, pundits argue that because China owns the lion’s share

of US Treasuries, about $1.2 trillion, the “nuclear option” would be for

China to dump its US Treasuries which would immediately raise interest

rates because the new buyers would require an incentive to sop them up.

Rising rates would increase the value of the USD. Mission accomplished. I

don’t think the Chinese would ever do this, for a couple of reasons.

First, as long as the dollar remains the reserve currency, China will

need dollars to buy commodities and to build infrastructure – such as

those needed for the New Silk Road. Second, by buying Treasuries, China

must print a lot of yuan, which decreases in value as it is used for

international exchange purchases. The yuan is kept low. US bonds are

also extremely liquid, so if China needed cash quickly, they could

easily find buyers for them.

Jeffrey Frankel, a Harvard prof who writes for Project Syndicate, says that China doesn’t need to sell any Treasuries to win a trade war with the US.

All China needs to do is say it’s planning to cut back on Treasury

purchases. We saw this earlier this year. A rumoredslowing of Chinese

Treasury purchases immediately crashed bond prices and hiked yields.Falling

bond prices usually signal a higher inflationary environment which

would mean higher interest rates and increased stock market volatility.

Frankel

and others also point out that while the Trump Administration frets

over the trade deficit with China, what really matters is China’s

current account surplus with the US, which has actually been falling

since 2008 (the trade deficit is the largest component of the current

account deficit which includes interest and dividends, and foreign aid).

The recent Republican tax cuts are said to increase the current account deficit with China:

Simply

put, the Republicans’ tax law – which emphasizes big cuts, especially

for corporations and the highest-income earners – is virtually certain

to widen the budget deficit and, in turn, increase the current-account

deficit. Trump’s legislative victory implies the return of the infamous

twin deficits that followed George W Bush’s tax cuts of 2001 and 2003,

and Ronald Reagan’s cuts of 1981-1983. - The Guardian

Another

factor likely to weigh on the dollar is Trump’s promised infrastructure

bill which should generate around $1.5 trillion. How will this be

financed? The likelihood is the issuance of more Treasury bills, which

will also be needed to finance the tax cuts. That would keep driving the dollar down,

along with bond yields (demand for T-bills goes up which raises their

prices and yields drop inversely) meaning a flight of capital to

emerging markets, like China. The 10-year yield in January jumped above 2.7%, its highest level since 2014.

Others argue that the US could win a currency war.

According to the Pimco Blog the US is engaged in a “cold currency war” and it is winning.Why?

Because Trump “carries the bigger stick” of protectionism. China seems

to have more to lose in a trade and currency war, with a smaller economy

than the US – $13.09 trillion compared to $20.2 trillion.

Author

Joachim Fels also states that other parties in this trade dispute, like

the EU and Japan, have done nothing so far to defend their economies

against rising currencies and tariffs – both the Bank of Japan and the

European Central Bank have trimmed bond purchases which should

strengthen their respective currencies against the dollar.

Effects of a low dollar

A

strong currency is generally thought to be good for the US economy

because it keeps interest rates low and inflation at bay. A strong

dollar however, as mentioned, is bad for exporters, but exporters are a

relatively low percentage of the total economy, around 13% versus 66%

for consumers. The more expensive import prices that result from a

weaker dollar, including gasoline, therefore hurt more Americans than

are helped by cheaper exports. Tourism of course rises and falls based

on the value of the dollar, with a weak dollar keeping more Americans at

home. Multinational firms that do a lot of manufacturing in the US, or

do business in countries whose currencies are beating the greenback,

will benefit from a low dollar.

The dollar and commodities

A

weak dollar usually means stronger commodities prices. Because the USD

is the reserve currency and most commodities are traded in dollars, the

value of the dollar is of crucial importance in determining the value of

the commodity in question. Take the case of a low dollar. When the

dollar drops it takes less of another currency to buy dollars needed to

purchase the commodity, so the demand for that commodity will increase.

The inverse happens when the dollar strengthens. The two graphs below

compare the USD Index for one year versus the Thomson Reuters/ Core

Commodity Index.

Gold

and the dollar also have an inverse relationship, though it’s a bit

more complicated than with other commodities because gold is an

investment instrument. When the dollar falls, gold tends to rise, but

this isn’t always the case. Inflation, or the threat of inflation,

economic and political upheavals, wars, and interest rate fluctuations

all affect the gold price, as well as supply and demand drivers. Lately

gold has risen as the dollar has fallen, but here have been other

factors Ie. the threat of a trade war dragging the dollar down at the

same time as propping up gold. In a trade war, as we have suggested, the

Chinese could start dumping US Treasuries to push the dollar up against

the yuan, and this would also be bullish for gold.

The dollar and mining

Whether

or not a mining or exploration company is profitable is often dependent

on currency fluctuations. Let’s take two examples: a Canadian gold

company operating in Brazil, and a Canadian oil and gas firm doing

business in the United States. In the first case, the company will pay

all of its gold mining costs in Brazilian reals, and with the Canadian

dollar stronger than the real, this means a significant cost savings –

the exchange rate is currently 1 Brazilian real for 0.37 Canadian

dollars. The company then produces gold that is priced in US dollars.

Even though the dollar is now low, it is still stronger than the

Canadian dollar, so when this company converts its USD revenue, it will

get another bump – currently an extra 26 cents for every USD it

exchanges to CAD. This firm should be quite profitable in this scenario.

In

the second case, suppose a Canadian company is drilling for oil in the

US. Now the Canadian oil explorer must pay all their expenses in USD,

which are 26% higher than if the operations were in Canada. When oil is

produced, dollars flow back to the firm, which are then converted to

Canadian, like in the first case, at a 26% premium. Imagine though that

the Canadian dollar appreciates in relation to the US dollar. Now the

company’s expenses drop, because less Canadian dollars need to be

converted into USD to pay its suppliers. Oil sales comes back as USD,

but now, converting them back to Canadian doesn’t yield the same

premium, maybe only 10% versus 26%. So a higher Canadian dollar helps on

the cost side but it could even out on the revenue conversion.

Conclusion

Currency

wars are not new, but the fact that this currency war is tied into the

trade dispute presently happening with China, and at the same time a

series of geopolitical tensions that are making the threat of a real war

possible, makes this round of competitive devaluations particularly

interesting to follow. In the race to devalue the Chinese yuan versus

the US dollar, who would win? My bet is on China, simply because the US

has allowed itself to become so indebted to the Chinese Central Bank,

that any hint of selling off US Treasuries is bound to scare the bond

markets and raise yields, with a negative knock-on effect on the stock

markets, which fear inflation and interest rate hikes. The dollar would

have to rise.

But,

it’s also clear that the Trump Administration favors a low dollar in

order to keep exports competitive and to bring jobs back to America. How

far Trump is willing to go to make this happen remains to be seen. Like

in any war, there will be winners and losers, but so far it all looks

positive for commodities. I’ve got what a potential currency war and

what it does for commodities like gold, lithium and oil on my radar

screen. Do you?

If not, perhaps you should.