Mary Ward and the Institute of Mary

Foundress, born 23 January, 1585; died 23 January, 1645; eldest

daughter of Marmaduke Ward and Ursula Wright, and connected by blood

with most of the great Catholic families of Yorkshire. She entered a

convent of Poor Clares at St.-Omer as lay sister in 1606. The following

year she founded a house for Englishwomen at Gravelines, but not finding

herself called to the contemplative life, she resolved to devote

herself to active work. At the age of twenty-four she found herself

surrounded by a band of devoted companions determined to labour under

her guidance. In 1609 they established themselves as a religious

community at St.-Omer, and opened schools for rich and poor. The venture

was a success, but it was a novelty, and it called forth censure and

opposition as well as praise.

The first word that Mary Ward uttered was “Jesus”, after which she did not speak again for several months.

Her idea was to enable women to do for the Church in their proper

field, what men had done for it in the Society of Jesus. The idea has

been realized over and over again in modern times, but in the

seventeenth century it met with little encouragement. Uncloistered nuns

were an innovation repugnant to long- standing principles and traditions

then prevalent. The work of religious women was then confined to

prayer, and such good offices for their neighbour as could be carried on

within the walls of a convent. There were other startling differences

between the new institute and existing congregations of women, such as

freedom from enclosure, from the obligation of choir, from wearing a

religious habit, and from the jurisdiction of the diocesan.

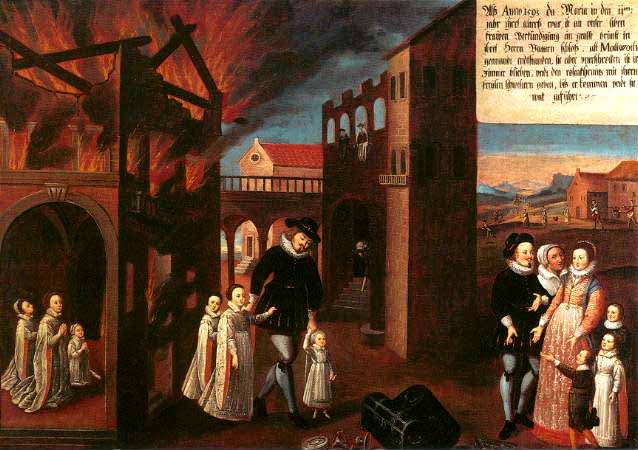

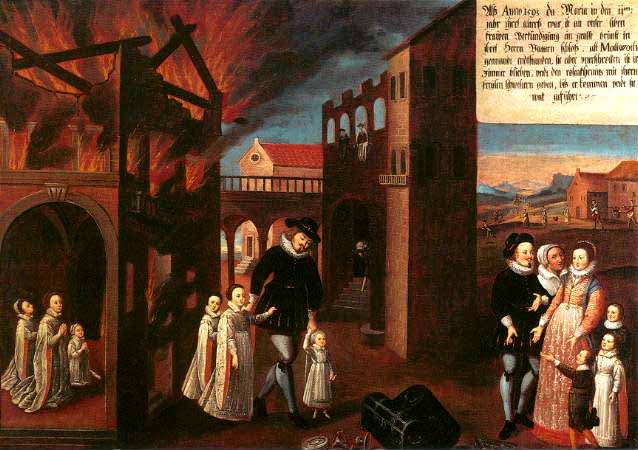

In

the year 1595, when Mary was in her eleventh year, on the feast of the

Annunciation, a great fire broke out at her father’s mansion at Mulwith.

She was not alarmed, but remained in a room, saying the rosary with her

sisters until their father came to fetch them.

Moreover her scheme was put forward at a time when there was much

division amongst English Catholics, and the fact that it borrowed so

much from the Society of Jesus (itself an object of suspicion and

hostility in many quarters) increased the mistrust it inspired. Measures

recognized as wise and safe in these days were untried in hers, and her

opponents called for some pronouncement of authority as to the status

and merits of her work. As early as 1615, Suarez and Lessius had been

asked for their opinion on the new institute. Both praised its way of

life. Lessius held that episcopal approbation sufficed to render it a

religious body; Suarez maintained that its aim, organization, and

methods being without precedent in the case of women, required the

sanction of the Holy See.

In

her thirteenth year, after overcoming many obstacles, Mary prepared

with great zeal and devotion for her first communion, on which occasion

she received much light and knowledge from God.

St. Pius V had declared solemn vows and strict papal enclosure to be

essential to all communities of religious women. To this law the

difficulties of Mary Ward were mainly due, when on the propagation of

her institute in Flanders, Bavaria, Austria, and Italy, she applied to

the Holy See for formal approbation. The Archduchess Isabella, the

Elector Maximilian I, and the Emperor Ferdinand II had welcomed the

congregation to their dominions, and together with such men as Cardinal

Federigo Borromeo, Fra Domenico de Gesù, and Father Mutio Vitelleschi,

General of the Society of Jesus, held the foundress in singular

veneration. Paul V, Gregory XV, and Urban VIII had shown her great

kindness and spoken in praise of her work, and in 1629 she was allowed

to plead her own cause in person before the congregation of cardinals

appointed by Urban to examine it. The “Jesuitesses”, as her congregation

was designated by her opponents, were suppressed in 1630.

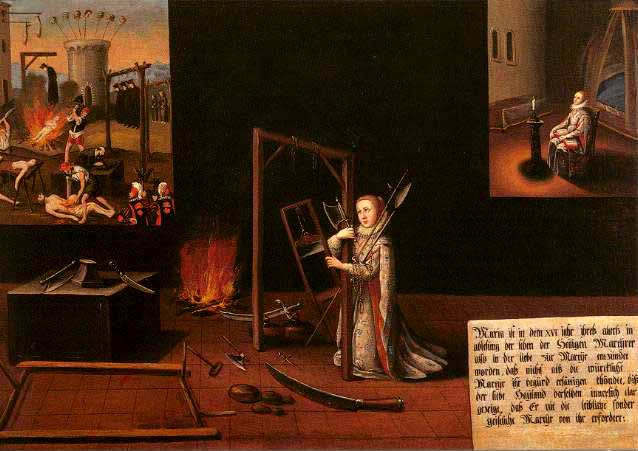

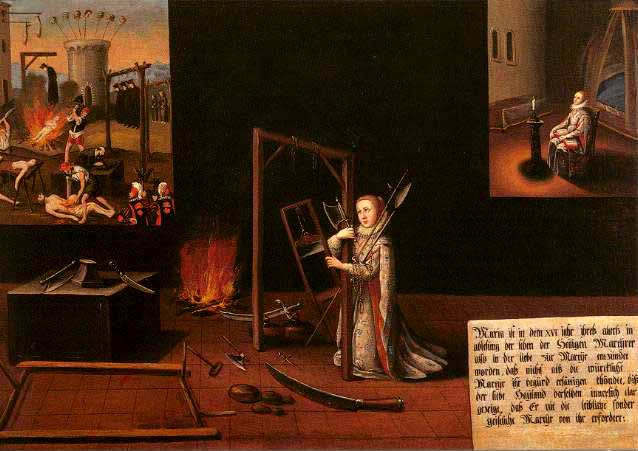

When

Mary was sixteen and read the lives of the holy martyrs, she was seized

with such a burning desire to follow their example that she felt only

martyrdom itself could satisfy her longing, until our Saviour revealed

to her interiorly that what He required of her was spiritual rather than

bodily martyrdom.

Her work however was not destroyed. It revived gradually and

developed, following the general lines of the first scheme. The second

institute was at length approved as to its rule by Clement XI in 1703,

and as an institute by Pius IX in 1877.

At the express desire of Pope Urban Mary went to Rome, and there as

she gathered around her the younger members of her religious family,

under the supervision and protection of the Holy See, the new institute

took shape. In 1639, with letters of introduction from Pope Urban to

Queen Henrietta Maria, Mary returned to England and established herself

in London. In 1642 she journeyed northward with her household and took

up her abode at Heworth, near York, where she died. The stone over her

grave in the village churchyard of Osbaldwick is preserved to this day.

For the history of the institute subsequent to the death of Mary Ward, see INSTITUTE OF MARY, below.

In

1606, Mary being then 21, left home with her confessor’s consent, and

took a ship to Saint-Omer accompanied by Mrs Bentley to whose care she

had been entrusted. Later in 1609, with the approval of her confessor

whom she had vowed to obey in all spiritual matters, she made a vow to

return to England and to labour there for the salvation of souls, in

conformity with her state. Her labours produced abundant fruit.

CHAMBERS, Life of Mary Ward (London, 1885); SALOME, Mother M. Mary Ward, A Foundress of the Seventeenth Century (London, 1901); MORRIS, The Life of Mary Ward in The Month,

LV. The oldest sources for the history of Mary Ward are the MS. lives

by WIGMORE (English), PAGETI (Italian, 1662. Nymphenburg Archives).

BISSEL (Latin, 1667 or 1668, of which there is a copy in the Westminster

Diocesan Archives), LOHNER (German, 1689, Nymphenburg Archives). The

most important of printed Lives are: KHAMM (1717); FRIDL (c. 1727), and

BUCHINGER.

_____________________________

The official title of the second congregation founded by Mary Ward.

Under this title Barbara Babthorpe, the fourth successor Mary Ward as

“chief superior”, petitioned for and obtained the approbation of its

rule in 1703. It is the title appended to the signatures of the first

chief superiors, and mentioned in the “formula of vows” of the first

members. “Englische Fräulein”, “Dame Inglesse”, “Loretto Nuns”, are

popular names for the members of the institute in the various countries

where they have established themselves. On the suppression, in 1630, of

Mary Ward’s first congregation, styled by its opponents the

“Jesuitesses”, the greater number of the members returned to the world

or entered other religious orders. A certain number, however, who

desired still to live in religion under the guidance of Mary Ward, were

sheltered with the permission of Pope Urban VIII in the Paradeiser Haus,

Munich, by the Elector of Bavaria, Maximilian I.

While

Mary was in London, her zealous words and gift of persuasion induced

her aunt Miss Gray to talk to a priest of the Society of Jesus with a

view to accepting the true faith. While there, Mary succeeded in

bringing back to the faith on her deathbed and obstinate heretic who

received the Holy Viaticum with great devotion.

Thence some of the younger members were transferred at the pope’s

desire to Rome, there to live with Mary Ward and be trained by her in

the religious life. Her work, therefore, was not destroyed, but

reconstituted with certain modifications of detail, such as subjection

to the jurisdiction of the ordinary instead of to the Holy See

immediately, as in the original scheme. It was fostered by Urban and his

successors, who as late as the end of the seventeenth century granted a

monthly subsidy to the Roman house. Mary Ward died in England at

Heworth near York in 1645, and was succeeded as chief superior by

Barbara Babthorpe, who resided at Rome as head of the “English Ladies”,

and on her death was buried there in the church of the English College.

She was succeeded as head of the institute by Mary Pointz, the first

companion of Mary Ward. The community at Heworth removed to Paris in

1650. In 1669 Frances Bedingfield, one of the constant companions of

Mary Ward, was sent by Mary Pointz to found a house in England. Favoured

by Catherine of Braganza, she established her community first in St.

Martin’s Lane, London, and afterwards at Hammersmith. Thence a colony

moved to Heworth, and finally in 1686 to the site of the present

convent, Micklegate Bar, York. In addition to that at Munich, two

foundations had meantime been made in Bavaria—at Augsburg in 1662, at

Burghausen in 1683.

During

her stay in London in 1609, Mary’s edifying life and persuasive words

won over several young ladies of noble birth to the service of the

Divine Spouse. Inspired by her example and to avoid the snares of the

world, they crossed over with her to Saint-Omer, to serve God in the

religious state under Mary’s direction.

At the opening of the eighteenth century the six houses of Munich,

Augsburg, Rome, Burghausen, Hammersmith, and York were governed by local

superiors appointed by the chief superior, who resided for the most

part at Rome, and had a vicaress in Munich. Thus, for seventy years the

institute carried on its work, not tolerated only, but protected by the

various ordinaries, yet without official recognition till the year 1703,

when at the petition of the Elector Maximilian Emanuel of Bavaria, Mary

of Modena, the exiled Queen of England, and others, its rule was

approved by Pope Clement XI. It was not in accordance with the

discipline of the Church at that time to approve any institute of simple

vows. The pope was willing, however, to approve the institute

as such,

if the members would accept enclosure. But fidelity to their

traditions, and experience of the benefit arising from non-enclosure in

their special vocation, induced them to forego this further

confirmation. The houses in Paris and in Rome were given up about the

date of the confirmation of the rule in 1703. St. Pölten (1706) was the

first foundation from Munich after the Bull of Clement XI. In 1742 the

houses in Austria and its dependencies were by a Bull of Benedict XIV

made a separate province of the institute, and placed under a separate

superior-general. The Austrian branch at present (1909) consists of

fourteen houses.

On

Christmas Day 1626, Mary attended Mass in the Capuchin Church at

Feldkirch and prayed most earnestly to the new-born Saviour for the

conversion of the King of England. God revealed to her the infinitely

tender love He had for the King and how much He desired him to share His

eternal glory, but that the King’s cooperation was wanting.

In Italy, Lodi and Vicenza have each two dependent filials. When the

armies of the first Napoleon overran Bavaria in 1809, the mother-house

in Munich and the other houses of the institute in Germany—Augsburg,

Burghausen, and Altötting excepted—were broken up and the communities

scattered. On the restoration of peace to Europe, King Louis I of

Bavaria obtained nuns from Augsburg, and established them at

Nymphenburg, where a portion of the royal palace was made over to them.

In 1840 Madame Catherine de Graccho, the superior of this house, was

appointed by Gregory XVI general superior of the whole Bavarian

institute. At the present day there are 85 houses under Bavaria, with

1153 members, 90 Postulants, 1225 boarders, 11,447 day pupils and 1472

orphans. Four houses in India, one at Rome, and two in England are

subject to Nymphenburg. The house in Mainz escaped secularization, being

spared by Napoleon on the condition that all connection with Bavaria

should cease. It is now the mother-house of a branch which has eight

filial houses.

In

1626, when Mary was on her way to Munich for the first time, not far

from the Isarberg she told her companions that God had revealed to her

in prayer that His Highness the Elector would provide them with a

suitable house and a yearly means of support. This effectively took

place soon after their arrival in Munich.

When vigour was reviving in the institute abroad, the Irish branch

was founded (1821) at Rathfarnham, near Dublin, by Frances Ball, an

Irish lady, who had made her novitiate at York. There are now 19 houses

of the institute in Ireland, 13 subject to Rathfarnham and 6 under their

respective bishops. The dependencies of Rathfarnham are in all parts of

the world—3 houses in Spain, 2 in Mauritius, 2 at Gibraltar, 10 in

India, 2 in Africa, 10 in Australia, with a Central Training College for

teachers at Melbourne (1906). There are 8 houses of the institute in

Canada, 3 in the United States, 7 in England, about 180 houses in all.

Owing to the variety of names and the independence of branches and

houses, the essential unity of the institute is not readily recognized.

The “English Virgins”, or “English Ladies”, is the title under which the

members are known in Germany and Italy, whilst in Ireland, and where

foundations from Ireland have been made, the name best known is “Loretto

Nuns”, from the name of the famous Italian shrine given to the

mother-house at Rathfarnham. Each branch has its own novitiate, and

several have their special constitutions approved by the Holy See. The

“Institute of Mary” is the official title of all; all follow the rule

approved for them by Clement XI, and share in the approbation of their

institute given by Pius IX, in 1877.

The Coat of Arms of Mary Ward over the Gateway in Mainz.

The sisters devote themselves principally to the education of girls

in boarding-schools and academies, but they are also active in primary

and secondary schools, in the training of teachers, instruction in the

trades and domestic economy, and the care of orphans. Several members of

the institute have also become known as writers.

M. LOYOLA (Catholic Encyclopedia)