Mass of the Catechumens:

From the Introibo to the Gloria

The Sacrifice of the Mass is the Sacrifice of the Cross itself. Only the

Priest can offer the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass and Transubstantiate

the host and wine into the Body, Blood, Soul and Divinity of Our Lord

Jesus Christ.

Woe, then, to the Priest who despises his office and

mission, who persecutes Christ or grieves Him. And how admirable is the

Priest who loves God and takes his responsibilities seriously.

This article in the series on the History of the Mass aims to offer an explanation of the Holy Mass to help the faithful keep their spirit attuned to the great events of the altar. There are two major movements in the Mass:

This article in the series on the History of the Mass aims to offer an explanation of the Holy Mass to help the faithful keep their spirit attuned to the great events of the altar. There are two major movements in the Mass:

- The first is the Mass of the Catechumens, which starts with the prayers at the foot of the altar and ends with the Creed.

- The second is the Mass of the Faithful which begins with the Offertory and ends with the Last Gospel.

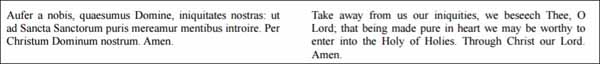

In the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass the first act of the Priest is to genuflect, make the Sign of the Cross and utter:

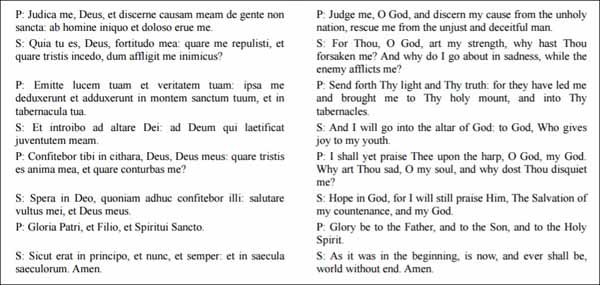

The Priest joins his hands and says the antiphon, Introibo ad altare Dei, as an introduction to the 42nd Psalm. This psalm was selected, Dom Gueranger tells us, because this verse was the most appropriate beginning to the Holy Sacrifice. The Church always selects the psalms she uses because of some special verse that best expresses what she wants to do or say. (1)

This psalm of David continues with the Judica me, Deus, a beautiful expression of a soul bespeaking his hope and joy in God. It is so filled with joy that the Holy Church omits it in Masses for the Dead and during Passiontide.

These are the supplications made to Almighty God to detach his thoughts from things of the world and his corrupt nature. Conscious of his own weakness, he trusts in "God his strength” and begs to be led by His “Light,” Our Lord Jesus Christ, the true light that enlightens every man that comes into the world, and by His “Truth,” the Spirit of Truth which proceeds from the Faith.

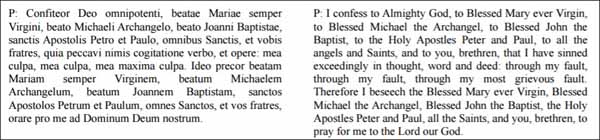

To acknowledge his unworthiness and past sins, the Priest bends low before the altar and strikes his breast three times at the mea culpa and prays the Confiteor:

This formula of confession most likely dates from the 8th century. Dom Gueranger insists, "We are not allowed to the make the slightest change in the words." For the recitation of this formula produces the forgiveness of venial sins, provided we be contrite for them. God, in His infinite Goodness, thus provides another way for us to be cleansed from our venial sins. (2)

The priest outwardly testifies his interior repentance, turning toward Mary and all the saints, as also to all the faithful present, begging that they also will all pray for him before God.

The Confiteor is said by the priest and, then, said by the acolytes on behalf of the faithful

The Confiteor is said by the priest and, then, said by the acolytes on behalf of the faithfulThe difference between the Confiteor of the Priest and the acolyte is only two words: the Priest says “vobis” and “vos”, the acolyte says “tibi” and “te”. Thus, contrition is made before the beginning of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass.

On the Cross, Our Lord took upon Himself the sins of the world to atone for them with His Blood; so now in each Mass the Priest and the congregation lays their sins upon Him that He may efficate them. For this reason also, the Priest says these prayers down at the foot of the altar, as if laden with the sins of the people before God, and begs his mercy.

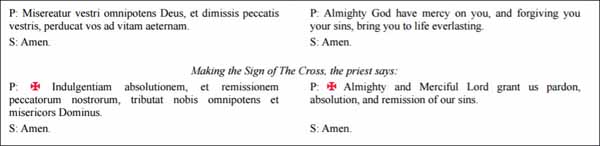

After the Priest hears the faithful, via the acolytes, acknowledge their sins, he invokes a blessing on them and, with the Indulgentiam, asks for himself and his brethren pardon and forgiveness of their sins:

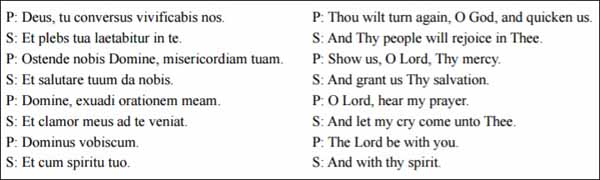

The confession being made, the priest again bows down, but not so profoundly as he did during the Confiteor, signifying that both he and the faithful are uplifted, knowing they have been forgiven their sins. Then he recites these comforting versicles:

When he asks that the Lord show us His mercy, these are the words of David in his 84th Psalm praying for the coming of the Messiah. By the word mercy, we ask that God vouchsafe to send us the One who is His Mercy and His Salvation ¬– that is, the Savior.

The priest ascends the altar like Moses on the mount

The priest ascends the altar like Moses on the mountThen the priest begins his ascent to the altar. Dom Guerenger compares the priest to Moses who takes leave of the people at the bottom of the mountain to ascend into the cloud to speak with God face to face.

It is a beautiful thought: The priest leaves the people to begin communion with God alone to effect the Sacred Mystery, and only descends the steps again when he will return, not with the stone tablets of Moses, but with the Sacred Host - which is Christ Himself - to give to the people.

As he ascends, he again asks pardon for him and all present, and says the following:

Bowing low over the Altar he kisses the Altar stone as a sign of respect for the saints' relics that are present within the stone itself. Again, another prayer for the pardon of his sins:

Introit and Kyrie

The Priest goes to the Epistle side, makes the sign of the Cross, and recites the first Proper - the Introit - which opens the readings. The Proper, a verse from the Psalms of the Old Testament that varies according to the feast celebrated or the season of the year, is often the key to understanding the Epistle and Gospel to follow.

On the feasts of Saints, the Introit reveals the outstanding work, martyrdom, etc. of the Saint being honored; on the various Sundays, the Introit introduces some truth of the faith, a Divine promise or recalls some inspirational event and is often a cry for mercy. For example, during Advent we express longing for Our Redeemer, at Christmas we rejoice at the Nativity of Our Lord Jesus, at Corpus Christi we give thanks for the infinite gift of the Holy Eucharist.

The Kyrie represents the nine choirs of Angels

The Kyrie represents the nine choirs of Angels praising God

The first three invocations are addressed to the Father, who is Lord: Kyrie eleison (from the Greek, “Lord have mercy”). The next three are addressed to Christ, the Son Incarnate: Christe eleison. The last three are addressed to the Holy Ghost, Kyrie eleison, who is Lord together with the Father and the Son. "The Son, of course, is equally Lord with the Father and the Holy Ghost," Dom Gueranger explains, "but Holy Church here gives HIm the title of Christ because of the relation this bears to the Incarnation." (3)

There is another beautiful symbolism in the three invocations, each repeated thrice. They represent our union here below with the nine choirs of angels who sing in Heaven the glory of the Most High. This union prepares us to join with the angels in their prayer of rejoicing in announcing the glad tidings of Christ's birth, the Gloria in excelsis Deo.

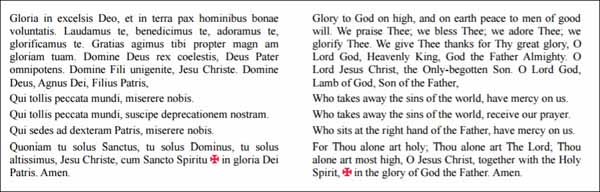

The Priest standing in the same place at the center of the Altar, extends his hands, raises them and intones the Gloria in excelsis Deo. The Gloria is a sublime hymn of praise dating from the earliest days of the Church, a joyful welcome to our Savior who is soon to be born upon the Altar as he was born in the cave of Bethlehem:

At the word “Deo,” the priest joins his hands and bows to the Crucifix. Then, standing erect, he continues to the end with his hands joined. He bows his head at “Adoramus te”, “Cristus agamus tibi”, “Jesu Christe”, and “Suscipe deprecationem nostram.” At the end, he makes the Sign of the Cross when he says “cum Sancto Spiritu.” (4)

To be continued

- Dom Prosper Guéranger, Explanation of the Holy Mass, 1st ed. 1885, rep. Loreto Publications, 2007, p. 3.

- The Abbot of Solesmes Abbey also tells us: "In reference to this formula of confession, which has been established by our Holy Mother the Church, it may be well to remind our readers that it would, of itself, suffice for one who was in danger of death and unable to make a more explicit confession." Ibid., p. 5-6.

- Ibid., p. 16.

- The “Gloria” being a hymn of praise as omitted in Masses for the dead, during Advent and Lent and on other occasions where expression of joy is not appropriate.