The “Hate” Canard: Is Opposing Sexual Immorality and its Purveyors a Matter of “Hatred”?

SOURCE

Contemporary man has long replaced reason with emotion. This is why we see such absurd phenomena as transgenderism in our day. It is also the reason why those who defend the natural law and the completely rational idea that there cannot be more than one true religion, are accused of “hate/hatred”, “anger”, “fear/phobia”, “insanity”, or “extremism.” People have simply lost (or never learned) the ability to reason and to reason correctly. They prefer to feel instead. And whatever makes them feel bad, is bad.

This phenomenon is widespread in Western society, and the average pewsitter in the Novus Ordo Sect as well as its leftist apologists, academics, and pundits are no exception.

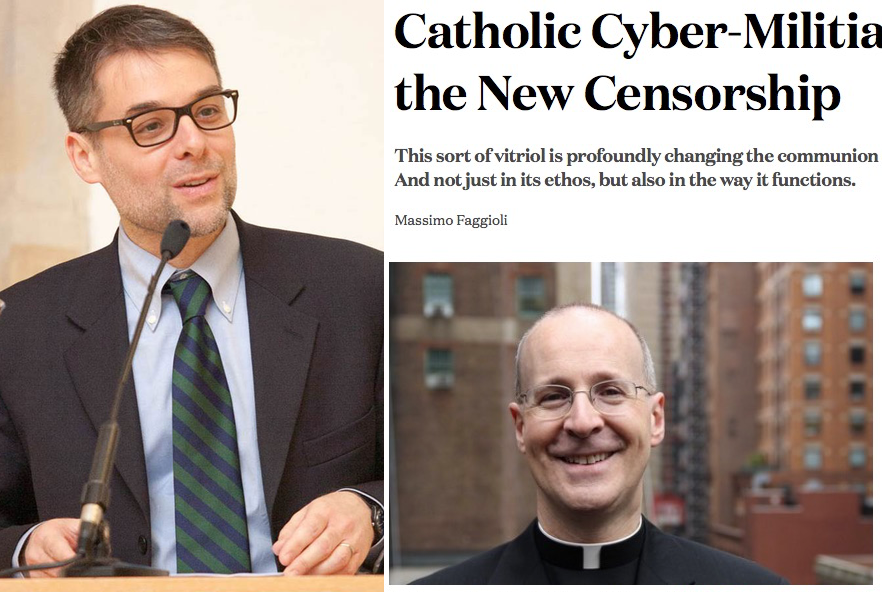

Take Massimo Faggioli, for example, an Italian historian, theologian, and author who teaches at Villanova University in the United States and writes for various online publications. He is upset at the fact that the homosexualist Jesuit “Fr.” James Martin — appointed five months ago by “Pope” Francis as consultor for the Vatican Secretariat for Communications — has recently gotten severe backlash from various culture warriors on and off the internet who are sick and tired of the perversities Martin promotes, defends, or happily tolerates (the latest being his idea that sodomites should be allowed to kiss one another at “Mass”).

Earlier this year, Martin — also known as “Hellboy” — published the book Building A Bridge: How the Catholic Church and the LGBT Community Can Enter into a Relationship of Respect, Compassion, and Sensitivity. That the book is building a bridge to hell does not bother the author in the least, and of course his infernal work has received the endorsement of Vatican “Cardinal” Kevin Farrell, Francis’ new frontman for family and life issues, as well as that of other “Catholic” pseudo-authorities.

With all the bridge building, however, it looks like a few bridges have now been burned for Martin. Not everyone is willing to sit idly by as Hellboy carries his perverts’ gospel to the ends of the earth. In fact, opposition to “Fr.” Martin has recently become so vociferous that he has had a number of previously-scheduled speaking engagements canceled, as reported by Church Militant, the conservative Novus Ordo news site famous for slamming and exposing everyone except “Pope” Francis.

Clearly displeased by these developments, Faggioli published his article “Catholic Cyber-Militias and the New Censorship” in the Sep. 18, 2017 edition of La Croix International. To attack Martin’s opposition, Faggioli uses the the favorite leftist vocabulary: Those who vehemently oppose Hellboy and try to neutralize his infernal influence against a wicked, timid, or indifferent Novus Ordo episcopate are “cyber militants” (whatever that means) and “extremists” (ooh!) that are part of a “fringe” (like the early Christians?) and who are filled with “anger” (righteous or unrighteous?) and “hatred” (definition, please?) and “intimidate” (justly or unjustly?) those who invite the pristinely orthodox butterfly of luv, James Martin, to speak at their event.

We note, too, that Faggioli accuses those evil cyber crusaders (whose intent is only to defend orthodoxy and good morals) of “verbal violence” — a term that, once again, appeals to the emotions rather than to reason, thus dispensing with the need for clear definitions and sound argumentation. Besides, using a term like “verbal violence” allows Faggioli to insinuate guilt by association with those who are physically violent — a connection entirely unwarranted but, one may suspect, not entirely unintended by the author. The consequences of such rhetoric could soon be disastrous — and yet, he is the one complaining about “censorship”.

With all the accusations of “hate” or “hatred” constantly being thrown at real Catholics and others who upset or threaten the politically correct social mores, it is time we took a good look at the real meaning of hate. What is the definition? What actually constitutes (and therefore doesn’t constitute) real hatred?

The following is an excerpt of what is perhaps the best, most exhaustive, and most up to date pre-Vatican II moral theology manual in the English language: Moral Theology: A Complete Course Based on St. Thomas Aquinas and the Best Modern Authorities by the Dominican scholars Fr. John A. McHugh and Fr. Charles J. Callan (imprimatur 1958). It is available in print (volume 1 here and volume 2 here) and in electronic format.

Here is what Fathers McHugh and Callan write about the sin of hate, first considered in general and then specifically with regard to one’s neighbor (we’ll skip hatred of God):

1296. Hate.—Hate is an aversion of the will to something which the intellect judges evil, that is, contrary to self. As there are two kinds of love, so there are also two kinds of hate. (a) Hatred of dislike (odium abominationis) is the opposite of love of desire, for, as this love inclines to something as suitable and advantageous for self, so hatred of dislike turns away from something, as being considered unsuitable and harmful to self. (b) Hatred of enmity (odium inimicitiæ) is the opposite of love of benevolence, for, as this love wishes good to the object of its affection, so hatred of enmity wishes evil to the object of its dislike.Such are the facts about the nature of hatred. One can easily see that this has nothing whatsoever per se to do with defending the moral order against perverts and their abettors and working to prevent the advance of their wicked ideology through legal and morally licit means.

…

1304. Hatred of Creatures.—All dislike of God is sinful, because there is nothing in God that merits dislike. But in creatures imperfections are found as well as perfections.

(a) Hence, dislike of the imperfections of our neighbor (i.e., of all that is the work of the devil or of his own sinfulness), is not against charity, but according to charity; for it is the same thing to dislike another’s evil as to wish his good. Thus, God Himself is said to hate detractors, that is, detraction (Rom., i. 30), and Christ bids His followers hate their parents who would be an impediment to their progress in holiness, that is, the sinful opposition of those parents (Luke, xiv. 26). Only when dislike is carried beyond reason is it sinful. Thus, a wife who dislikes her husband’s habit of drunkenness so much that she will not give him a necessary medicine on account of the alcohol it contains, carries her dislike to extremes.

(b) Dislike of the perfections of nature or of grace in our neighbor (i.e., of anything that is the work of God in him), is contrary to charity. Thus, God does not hate the detractor himself, nor should children ever hate the person of a parent, or the natural relationship he holds to themselves, no matter how bad the parent may be. As St. Augustine says: “One should love the sinner, but hate his vices.”

1305. The same principles apply to dislike of self. (a) Thus, one should dislike one’s own imperfections, for they are the enemies of one’s soul. So, contrition is defined as a hatred and detestation of one’s vices, and it is a virtue and an act of charity to self. (b) One should not dislike the good one has, except in so far as it is associated with evil. Thus, one should not regret one’s honesty, even if by reason of it one loses an opportunity to make a large sum of money; but one may regret having married, if one’s choice has been unfortunate and has made one’s life miserable.

…

1308. Is it ever lawful to wish evil to self or to others? (a) It is not lawful to wish anyone evil as evil, for even God in punishing the lost does not will their punishment as it is evil to them, but as it contains the good of justice. Hence, it is contrary to charity to wish that a criminal be put to death, if one’s wish does not go beyond the sufferings and loss of life the criminal will endure. (b) It is lawful to wish evil as good, or, in other words, to wish misfortunes that are blessings in disguise. Thus, one may wish that a neighbor lose his arm, if this is necessary to save his life.

1309. One may easily be self-deceived in wishing evil to one’s neighbor under the pretext that it is really good one desires, for the true intention may be hatred or revenge. Hence, the following conditions must be present when one wishes evil as good:

(a) On the part of the subject (i.e., of the person who wills the evil), the intention must be sincerely charitable, proceeding from a desire that the neighbor be benefitted. Thus, it is lawful to wish that a gambler may meet with reverses, if what is intended is, not his loss, but his awakening to the need of a new kind of amusement. St. Paul rejoiced that he had made the Corinthians sorrowful, because their sorrow worked repentance in them (II Cor., vii. 7-11). Of course, the desire of a neighbor’s good does not confer the right to wrong him, for the end does not justify the means.

(b) On the part of the object (i.e., of the evil which is wished to another), it must be compensated for by the good which is intended. It is not lawful to desire the death of another on account of the property one expects to inherit, for the neighbor’s life is more important than private gain; but it is lawful to wish, out of interest in the common welfare, that a criminal be captured and punished, for it is only by the vindication of law that public tranquillity can be secured (Gal., v. 12).

1310. Is it lawful to wish the death of self or of a neighbor for some private good of the one whose death is wished? (a) If the good is a spiritual one and more important than the spiritual good contained in the desire to live, it is lawful to desire death. Thus, it is lawful to wish to die in order to enter into a better life, or to be freed from the temptations and sinfulness of life on earth. But it is not lawful to wish to die in order to spare a few individuals the scandal they take from one’s life, if that life is needed by others as a source of edification (Philip., i. 21 sqq.). (b) If the good is a temporal one but sufficiently important, it does not seem unlawful to desire death. Thus, we should not blame a person suffering from a painful and incurable disease, which makes him a burden to himself and to others, if, with resignation to the divine will, he prays for the release of death; for “death is better than a bitter life” (Ecclus., xxx, 17). But lack of perfect health or a feeling of weariness is not a good reason for wishing to die, especially if one has dependents, or is useful to others.

1311. Is it ever lawful to wish spiritual evil to anyone? (a) Spiritual evil of iniquity may never be desired, for the desire of sin, mortal or venial, is a sin itself (see 242), and it cannot be charitable, for charity rejoiceth not with iniquity (I Cor., xiii. 6). It is wrong, therefore, to wish that our neighbor fall into sin, offend God, diminish or forfeit his grace, or lose his soul. On the contrary, we are commanded to pray that he be delivered from such evils. (b) The good that God draws out of spiritual evil may be desired. Some are permitted to fall into sin, or be tempted, that they may become more humble, more charitable, more vigilant, more fervent. It seems that the permission of sin in the case of the elect is one of the benefits of God’s predestination, inasmuch as God intends it to be an occasion of greater virtue and stronger perseverance. It is not lawful to wish that God permit anyone to fall into sin, but it is lawful to wish that, if God has permitted sin, good will follow after it.

(Fr. John A. McHugh & Fr. Charles J. Callan, Moral Theology, vol. 1 [New York, NY: Joseph F. Wagner, 1958], nn. 1296, 1304-1305, 1308-1311)

We must also keep before us that hate can be a motive but it can never be a physical action (unlike stealing, adultery, or calumny) — yet this is precisely what it is gradually being injected into the public’s consciousness as.

Applied to the case of “Fr.” Martin: To say that contacting a “Catholic” university and asking them to cancel a speaking engagement for someone who promotes grave immorality, constitutes “hate”, is sheer nonsense. It is rhetoric, not rational argumentation. Although one could claim that hate is the motive for such an action, this would at least be rash because it would impugn the moral character of the agent without sufficient evidence. After all, any number of motives other than hate — understood in the proper sense of the term as defined above — could be envisioned.