The 1956 Reform Triggered Many Others

1958: Pius XII - De Musica Sacra – Instruction on Sacred Music

In 1958 Pius XII creates foundation for Novus Ordo

For the first time in the History of the Church, the lay faithful were given, by official decree, a direct and active role in the performance of the liturgy. The following references from De musica sacra show that members of the congregation could henceforth, “by right,” perform the following:

At Solemn (Sung) Mass:

• § 25a: Sing the liturgical responses to the priest.

This was only the lowest of several graded steps of increasing complexity for the “active participation” of the congregation;

• § 25b: Sing the parts of the Ordinary: Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus-Benedictus, Agnus Dei.

But Pope Pius X had taught that these were the provinces of the clergy and the choir. Contrary to majority opinion, he had given no directives for “congregational singing” of liturgical texts; (2)

The beginning of the end of the quiet Mass...

This was an astoundingly radical innovation. There is no historical precedent for congregational singing of the Propers. These had been sung by specially trained choirs since at least the 7th century.

• § 13b, c: Sing liturgical texts in the vernacular with special permission.

Pius XII had already conceded this to the German Bishops in 1943. (3) This practice of replacing Gregorian Chant and Polyphony with vernacular hymns, strictly forbidden at Solemn Mass, soon became widespread as more Bishops requested the same permission. It would inevitably undermine the preservation of the Church’s treasury of Sacred Music;

• § 14a: Add some popular vernacular hymns with permission from the local Bishop.

This was only the tip of a very large iceberg. For, as Bugnini revealed, the original intention was that “the principle of songs in the vernacular is to be extended to the entire Church in the reformed Roman Missal. (4) Already in 1958, permission was available for the faithful to sing their favorite number in the vernacular during solemn Mass.

• § 27c: Recite the three-fold Domine, non sum dignus together with the priest before receiving Communion.

• § 96: A Commentator (who may be a layman) could exercise a liturgical ministry by standing in front of the congregation and audibly explaining the different parts of the Mass.

Mixed choirs today are promoted even among traditionalists for Tridentine Masses

• § 96a: Women were accorded the right to “lead the song and prayers of the faithful.”

This had always been the established practice in Protestant liturgies;

• § 100: Women and girls were permitted to join “mixed” choirs or form their own all-female choir to sing the liturgy.

Yet Pius X had authoritatively stated the traditional teaching that women cannot be admitted to liturgical choirs. (5)

At Low Mass:

• § 31a, b: Make the liturgical responses to the prayers of the priest, “thus holding a sort of dialogue with him.”

This included all the responses said by the server, including the Confiteor;

• § 31c: Say aloud with the priest all the parts of the Ordinary as at Sung Mass noted above.

Nothing could be more calculated to destroy the atmosphere of the “Quiet Mass” than an incessant stream of audible responses from the congregation.

• § 31d: Recite together with the priest the parts of the Propers: Introit, Gradual, Offertory, Communion.

• § 32: Recite the Pater Noster, including the Amen, in unison with the priest.

This innovation was first introduced in the 1951 Easter Vigil and Good Friday reforms. The communal recitation of this prayer is found in Protestant traditions. In the traditional Catholic liturgy, it has always been a sacerdotal prayer and was neither said by the server nor sung by the choir.

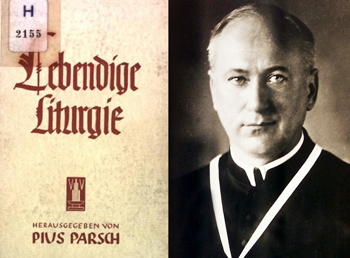

Already in 1938 Fr. Parsch was publishing works like Living Liturgy, introducing participation; below, a 1962 Betsingmesse celebrated in Germany

This particular point of the Mass, traditionally reserved for quiet reflection on one’s own unworthiness, was now “exteriorized” for all to hear.

• § 14b: Sing popular hymns or say aloud some prayers in the vernacular.

Thus, Pius XII rewarded the disobedience of innovators who had, against the rubrics, been promoting vernacular hymns and prayers in the Mass. For this purpose, Fr. Pius Parsch had devised the Betsingmesse (“Pray-Sing-Mass”) in the 1920s, which rapidly spread throughout the German-speaking lands and became the model for liturgical reformers in other countries.

An official approval was given in § 14b of the so-called “4-hymn sandwich,” interspersed among all the talking parts for the laity, which became ingrained in most parishes and still survives in the Novus Ordo.

• § 14c: A Lector could read the Epistle and Gospel to the faithful in the vernacular while the priest was reading them in Latin.

The point of the exercise was for the Lector (who could be a layman) to effectively “voice-over” the priest. This practice had already been popularized by Fr. Parsch’s Betsingmesse. A future step would be to have vernacular-only readings, for which the liturgical reformers had long been clamoring.

Unlike the Holy Week reforms, these reforms were only permissive rather than prescriptive, which explains why users of the 1962 Missal do not always follow them. Yet their effect was unfavorable to Tradition.

The 1958 Instruction was approved by Pius XII “in forma specifica,” indicating his personal involvement in the preparation of these revolutionary reforms. Henceforth, traditionally-minded priests were placed on the back foot, as it were, with the onus on them to provide a rationale for their continued use of the Church’s traditions.

1960: John XXIII – Rubricarum Instructum – New Code of Rubrics

Whereas the “sit-and-listen” ruling for the celebrant previously applied only to the Scripture readings in the 1956 Holy Week services, this was extended to all sung Masses from January 1961, when the New Rubrics came into effect. Here it was stipulated that “In sung Masses, all that the deacon, or subdeacon, or lector sing or read by virtue of their office is omitted by the celebrant.” (§§ 473, 513-514)

1964: Paul VI – Inter Oecumenici

– Implementation of the Liturgy Constitution

Archbishop Piero Marini, who had worked under Bugnini in the secretariat of the Consilium (the Commission that designed the Novus Ordo), described this Instruction as “a victory for the Consilium’s approach to liturgical reform.” (6) It is not difficult to see why.

Archbishop Marini, Master of Liturgical Celebrations under JPII & Benedict XVI

“The parts belonging to the choir and to the people [Partes quae ad scholam et ad populum spectant] sung or recited by them are not said privately by the celebrant.” (§ 32)

In this reform, which could be aptly termed Bugnini’s “Operation Switcheroo,” the celebrant becomes the “mute spectator” while the people become directly responsible for proclaiming parts of the Mass that had traditionally been invested in the celebrant.

However, as a sort of consolation prize, Inter Oecumenici condescendingly granted that “The celebrant may sing or recite the parts of the Ordinary together with the congregation or choir” (§ 48b), i.e. as if he were an ordinary member of the assembly.

To be continued

- J.B. O'Connell, Sacred Music and Liturgy, London, Burns and Oates, 1959, p 13.

- See here and here.

- In 1943, Pius XII capitulated to the German Bishops’ demands and allowed the High Mass (Deutsches Hochamt) to be sung in German by the congregation. The congregation sang most of the Mass texts in translation or paraphrase, even though this was strictly against the rubrics and the prescriptions of Canon Law. See here

- Annibale Bugnini, The Reform of the Liturgy, p. 903.

- Pius X, Tra le Sollecitudini, 1903, § 13.

- Piero Marini, A Challenging Reform: Realizing the Vision of the Liturgical Renewal, 1963-1975, Liturgical Press, 2007, p. 81.