Nine Things You Didn’t Know Were Medieval

From vegetarian meat substitutes to beach parties – find out what came from the Middle Ages!

Margarete Peutinger

Humanist power couple Konrad and Margarethe Peutinger might just be the OG stage parents. They saw themselves as at the helm of an Augsburg ascendant in the cadre of elite, wealthy, learned European cities. So when they learned that the Holy Roman Emperor would be in town soon, in 1503 they prepared. Or rather, they prepared their, Juliana, who had just turned three. Konrad and Margarethe devoted most of a year to forcing their toddler to memorize a Latin oration. She was to serve as a exemplar of what a fine, classical city Augsburg was, that even a little child, even a female child could be so well educated. When her parents finally paraded her before the emperor to say her piece, Maximilian asked little Juliana what she wanted for her achievement. The answer? Just a doll—a toy to play with.

Oh, and when Juliana died just a couple years later, Konrad and Margarethe repeated the same tricks on a smaller scale with their next daughter.

2. Steampunk Fashion

The wheel of fortune is a recurring theme in medieval literature and art: the goddess Fortuna, sometimes bald and sometimes blind, cranks her wheel around, cycling medieval people through the stages of fate: I will reign, I reign, I reigned, I have lost my kingdom. For most of the Middle Ages, though, artistic depictions of the rota fortunae and other crank/gear machines have a problem: they can’t possibly work. Western Europe had lost the knowledge of how to work gears and cranks.

As this knowledge filtered back into the west from the Muslim world in the late Middle Ages, one of its most visible and prestigious applications was the mechanical clock. Clocks and their components came to serve as markers of prestige, whether that meant a gorgeous city clock on a church or civic building, or a timepiece in the background of a royal portrait.

And in some cases, it even meant fashion. In fifteenth-century Italy, it was all the rage to display clocks and clock parts on one’s clothing at parties. Beatrice d’Este, wife of Milan’s soon-to-be duke, had a special request for her dress for a 1488 ball. The clock she wore, she insisted, not only had to function, it had to ring the hours.

3. Air pollution

From nineteenth-century London pea soup fog to twenty-first century China, we associate clogging, choking smog with industry, factories, and cramped urbanization. But as a growing medieval population burned through its wood supply for fuel and construction, households and workshops increasingly turned to coal as an alternate fuel. In 1307, a royal decree barred the brewers, potters, and bakers of London from burning coal instead of wood or charcoal in their ovens, citing complaints from all levels of the population that “an intolerable smell diffuses itself throughout the neighboring places, and the air is greatly infected…to the detriment of bodily health.”

4. Playing pretend

Byzantine religious writing, as John Duffy and Brigitte Pitarakis have highlighted, is packed with references to children playing pretend. For example, little Athanasius of Alexandria—yes, that Athanasius—was caught playing on the beach with some friends. What was their game? Bishops and baptizees. A little later, Damascene-Egyptian monk John Moschos told a similar story about children in his neighborhood. Their chosen sacrament to playact was not baptism but the Eucharist, reflecting their own exposure to church ritual.

Naturally, theological writers are thrilled by these events, viewing them as prophetic for the future sanctity and fruitful religious careers of the children involved. In the west, however, writers tended to take a more pragmatic approach. When children in the streets are playacting at war, the collection of semi-satirical proverbs known as the Distaff Gospels remarks archly, you can count on actual war being not far in the future.

5. Vegetarian meat substitutes

When teenagers and adults turn vegetarian or vegan today, there are two basic strategies for crafting a diet that is not just piles of grilled cheese and spaghetti. The first is to explore the exciting world of foods that are vegetarian from the ground up—wonderful bean and vegetable and grain based dishes from cultures around the world. The other is to entrench oneself in the world of meat and dig into vegetarian substitutes for hamburgers, hot dogs, chicken fingers, sausage, turkey, and once I even saw vegetarian “canned tuna” which WHY.

By the time medieval people started writing original cookbooks in the fourteenth century, of course, they had had centuries to get used to not eating meat on Fridays, during Lent, and on other fasting days. Surely the powers of culinary creativity would be unleashed for extra special dishes. And yet, recipe after recipe for meat dishes like lasagna simply includes the “Lent” variation. For the most part, this meant creating a vaguely meat-looking, though clearly not – tasting, substitute out of ground-up nuts.

The other option, of course, was to flat-out purchase an exemption to fasting rules from one’s parish, which takes “there is no such thing as ethical consumption” to a whole new level.

6. The slap-slap sound of flip-flops

One of my favorite religious-legal anecdotes comes from ninth-century al-Andalus, on the subject of women’s attire. The extent to which medieval Muslim (and Greek Christian) women wore veils in public is a hotly debated topic, given both the fragmentary source record and the modern political implications. Right now, most scholars hazily stipulate that veiling in public and/or seclusion at home were religious ideals and, more to the point, a class privilege. It was a social marker of great success for a man to be able to support a wife/wives/concubines who did not have to conduct business outside the home to support the family. This seems like a very male take on an intimately woman’s issue, so let’s turn to famed jurist Yahya ibn ‘Umar:

Yahya was asked about a kind of

sandal or flip-flop. Are shoemakers forbidden to make them? Because

women look for these flip-flops on purpose, with the intention of

wearing them…in public. And so it happens that, if a man is

absent-minded, when he hears these “chirping” mules he raises his head.

Assuming this scenario reflects actual practice (and later, similar versions seem to suggest so), the humble slap-slap or flip-flop

noise opens a sliver of a window into the piety of medieval Muslim

women. It would seem to suggest that women adopted whatever veiling

practices were typical, preserving their modesty in one-on-one

interactions. And yet they resisted the interpretation that veiling was a

way to symbolically erase them from public presence: the sound of their

sandals insisted on their presence.7. Beach parties

For all the wonderful beach coastline of Europe and North Africa, we don’t hear a lot about “fun in the sun” in medieval sources. The early references to building sand castles and to collecting seashells are distinctly classical, not medieval—and even the seashell collection is a sad bit of polemic/satire, as failed general Caligula irrationally orders his men to gather shells as “war booty.” In fact, medieval shoreline stories tend to involve dead bodies, whether it’s a ghost come to warn someone not to sail because their ship is going to capsize (spoiler: it does), or Scandinavian practices of burying the bodies of the disgraced dead on the edge of the beach as a sort of no man’s land.

But you know who knew how to party on the beach? The Muslims of Sicily and North Africa. One famous account has a group of raiders/pirates roll up to the Apulian shore in the mid-eleventh century. They demand tribute from the people of Salerno in exchange for, well, for destroying everything they hold dear including their own lives. While Christian officials are off dutifully and fearfully gathering money and goods to pay off the raiders,

[The raiders] gave themselves up to feasting and mirth on the plain between the city and the sea.

Unfortunately for our picnickers, though, Orderic Vitalis goes on to explain how the strong brave manly Normans did what the Italians couldn’t, and kicked them off the beach and back out to sea.8. Snowmen

Medieval snowball fights are fairly well known these days thanks to the Internet popularity of some depictions of them. But if snow can be packed into a ball, people knew, it could surely be sculpted into something much more significant.

One story about St. Francis of Assisi portrays snowmen as anything but fun. Overcome by lust in the middle of one winter’s night, Francis rushes out naked into the snowy garden. He makes seven shapes out of snow to represent the household he might have: his wife, his children, his servants. But they are people made of snow: they are dying of cold, and naked Francis does not even have his own cloak to give them. The lesson Francis taught himself, according to hagiographer Bonaventure, is that he could not serve seven masters, he could only serve the one true Master. The lesson for modern sensibilities is usually, let’s focus on the stories about Francis and animals, mmkay?

But snowmen were not always so grim. The winter of 1510-1511 was exceptionally harsh in the Low Countries, according to chroniclers, but the good people of Brussels made the best of it. From January into February, the craftsmen of the town organized a veritable snowman festival. All over the city, they lovingly constructed snow into works of art—heroes of classical mythology, religious symbols like a young woman with a unicorn in her lap (symbolizing virginity), profane amusements like a man caught in the act of defecating.

And this time, if the surviving poetry (poetry) about the snow art festival can be believed, the idea of the naked snow people freezing to death without clothing was something of a running joke.

9. Lazy students

Medieval scholars and readers attached enormous importance to the view of earlier authorities. Scholastic treatises are storehouses of earlier opinions on a given topic. And as later researchers discovered somewhat to their dismay The Travels of John Mandeville, one of the most popular books in the entire Middle Ages, comes neither from travels nor from John Mandeville. It’s almost entirely a compilation of excerpts from earlier, even well-known narratives.

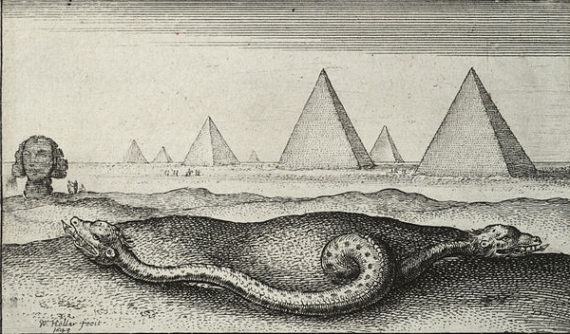

But this bog-standard practice fared rather poorly for one 12th century North African student. Upon returning home after making his hajj to Mecca, his teacher demanded, “Tell me about the pyramids of Egypt and what you saw of them, not what you have been told.” Sorrowfully, the student had to reply, “I have nothing of direct observation to say.”

Also medieval: teachers who don’t put up with that. Because, as al-Idrisi finishes, that student was right back off to the Nile to see and report on the pyramids for himself.