How Medieval Kings and Queens raised their children – an interview with Carolyn Harris

Carolyn Harris’ latest book Raising Royalty: 1000 Years of Royal Parenting

looks at the unique challenges of being parents to princes and

princesses. Covering the Middle Ages to modern times, Harris tells the

story of how kings and queens raised their children.

We interviewed the historian by email:Your book covers over a thousand years of history, going from the medieval to the modern. Why did you want to give readers such a wide-ranging view of the topic?

In 1973, Queen Elizabeth II visited Bath Abbey to celebrate the 1000th anniversary of King Edgar the Peaceable’s coronation in 973, which included the first example of the coronation rite that remains in use until the present day. The monarchy has survived for more than 1000 years (with a brief interregnum between 1649 and 1660) because it changed with the times but it’s also an institution rooted in tradition and I wanted to explore how those traditions developed since the emergence of a recognizable royal family in the public eye.

My own doctoral research examined public perception of the queen consort as a wife and mother informed my 2nd book, Queenship and Revolution in Early Modern Europe: Henrietta Maria and Marie Antoinette. I was fascinated by the change and continuity in both domestic and political life during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and wanted to explore these developments over longer period of time and wider range of royal families in the British Isles and elsewhere in Europe.

One common belief about Kings and Queens is that they were (and are) very aloof from their children, and that they showed little care or concern for them. Do you think this is true among the royal parents you wrote about?

Throughout my book, I examine the decisions of royal parents within the context of their times. There are parenting decisions that would be controversial today that were chosen with the best intentions in previous centuries. In medieval times, entrusting babies to wet nurses in country estates distant from the royal court was considered a necessary safeguard for a child’s health even though this practice might separate the child from his or her parents for months at a time. Nineteenth and early twentieth century tours of the British Empire then Commonwealth meant months of travel by sea, which was considered to be gruelling for children. Royal children accompany their parents on Commonwealth tours today because these tours are shorter and involve air travel.

In terms of the personal feelings of royal parents toward their children, there have been a variety of different kinds of relationships in both medieval and modern times. There are royal parents who took a close personal interest in the daily care of their children. When the future King Edward I fell ill as an adolescent while visiting Beaulieu Abbey, his mother, Henry III’s queen, Eleanor of Provence, ignored the Abbey’s restrictions on female visitors to care for her son. William the Conqueror’s queen Matilda of Flanders made clear that her first loyalty was to her eldest son Robert when he was at war with his father.

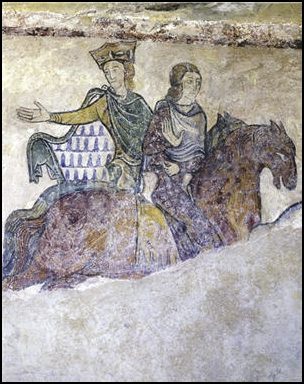

Eleanor

of Aquitaine on the left with a companion, probably Isabella of

Angoulême, from a mural in the Chapel of St. Radegund, Chinon

Of course, there were also cases of active hostility between royal children and their parents, which occasionally turned deadly. The first half of the eighteenth century saw a number of particularly dysfunctional royal families in power around the same time. In Britain, the House of Hanover was notorious for its conflicts between fathers and sons. In France, one of Louis XV’s daughters, Madame Louise, became a nun with the expressed purpose of redeeming her father’s soul and seeking forgiveness for his sins, which made a public statement that she disapproved of his dissolute lifestyle. In Russia, Peter the Great sentenced his son Alexei to death for treason and the heir died in prison. The eighteenth century was a time when more sentimental ideas of childhood were beginning to spread so the troubled royal households seemed particularly out of step with changing ideas, contributing to the lasting negative reputation attached to royal parenting.

What do you think is the most striking difference between how medieval royals and their modern counterparts in how they raised their children?

Prince

William of Wales; Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge and the Prince of

Cambridge leaving St. Mary’s hospital after the Prince’s birth – photo

by AshleyMott / Wikimedia Commons

In contrast, medieval royal children were trained for different roles in society depending on their gender and order of birth. In the eleventh century, royal women were sometimes more literate than men as the education of elder sons focused on military training. Matilda of Flanders was better educated than her husband, William the Conqueror and William’s contemporary, King Henry I of France marked his marriage contract with an X while his queen, Anna of Kiev, signed her name and title, “Anna Regina.” Younger sons were more likely to receive a scholarly education as the church was considered an acceptable career for junior members of the royal family (such as King Stephen’s younger brother Henry, the Bishop of Winchester). King Henry I and King John were both fourth sons who spent their early years receiving an ecclesiastical education.

By the sixteenth century, the educations of elite men and women had become more similar and all three of Henry VIII’s children, the future monarchs Mary I, Elizabeth I and Edward VI received a classical education. Humanist scholars of the time, however, debated whether certain skills, such as rhetoric, were necessary for women, even those in line to the throne. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the education of elite women focused more on courtly accomplishments and cultural patronage than languages, history and the classics. Both Queens Mary II and Anne became patrons of musicians but did not receive an classical education comparative to their predecessors Mary I and Anne. These differences between the educations of male and female members of the royal family have largely come to an end. In Sweden, Crown Princess Victoria undertook military training in 2003, part of the traditional education of male heirs to the throne.

How do you think the pubic/political pressure of having offspring/heirs affected the way royal couples approached parenthood?

For centuries, royal couples faced tremendous pressure to have children, especially male children, to ensure the political stability of their kingdoms. The ideal royal family size was two sons who survived to adulthood and a number of daughters to secure diplomatic alliances through their marriages. The absence of sons could prompt a succession crisis in medieval times while a large royal family – the thirteen surviving children of King George III or the nine children of Queen Victoria – prompted parliamentary debates about the cost of the royal family in more modern times.

The most famous examples of the pressure for royal parents to produce sons are the six wives of King Henry VIII. For Henry, who was only the second monarch from the Tudor dynasty, a legitimate son seemed essential and the fact that his first and second wives, Catherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn each produced a single, surviving daughter seemed to threaten the succession. In the late seventeenth century, Sarah Churchill, the Duchess of Marlborough marveled at Queen Anne’s determination to have a surviving child despite having “seventeen dead ones.” There was public sympathy for Queen Anne’s grief at the loss of her longest surviving son at the age of eleven but there were also biting satirical cartoons depicting her knighting any doctor who promised that she could still conceive.

In modern times, we still see examples of royal couples facing tremendous public pressure to have children. In Japan, the fertility struggles of Crown Prince Naruhito and Crown Princess Masako were discussed in the press. The couple was under particular scrutiny because the Japanese succession currently passes to male members of the Imperial family alone. In Europe, where most monarchies now follow absolute primogeniture, allowing the eldest child, male or female to succeed, we still see numerous examples of families of three or four children rather than one or two. Crown Prince Frederik and Crown Princess Mary of Denmark have four children and King Willem-Alexander and Queen Maxima of the Netherlands have three. The tradition of a larger royal family and public scrutiny royal parenting continues to the present day.

Dr. Carolyn Harris teaches history at the University of Toronto School of Continuing Studies and is the author of three books: Magna Carta and Its Gifts to Canada (Dundurn Press: 2015), Queenship and Revolution in Early Modern Europe (Palgrave Macmillan: 2015) and Raising Royalty: 1000 Years of Royal Parenting (Dundurn Press: 2017)