Silent Bible Revolution in the Vatican

Not all opinions expressed are that of TradCatKnight's. The New Mass is illicit and schismatic

Jerome’s Vulgate rejected by Rome after 1600 years

Rome – For more than a thousand years the Vulgate was the ‘authorized version’ of Western Christianity. Not anymore.Vatican II initiated a silent revolution which has now replaced the ancient Vulgate with a new translation. This new official Bible is no longer based on Latin manuscripts and lacks any historic worship tradition in the Church. This Nova Vulgata, as it is presented on the Vatican’s website, is a verse by verse reconstruction of what modernist scholars think the original Hebrew and Greek texts must have looked like.Is the Pope Catholic?

The Pope was Catholic and the Vulgate was the Bible of the Western Church. For centuries these were truths that were considered too ridiculous to question. In today’s context, rightly or wrongly, ‘Is the Pope Catholic?’ has taken on a new meaning, but for the Vulgate the situation is worse.

While the name suggests continuity, this Nova Vulgata is not a new or improved Vulgate edition. It is not even based on Vulgate manuscripts. Instead, the Nova Vulgata is a new translation into Latin. It is only presented as ‘New Vulgate’ because the Vatican has adopted it as the new authorized standard for Church and academia alike. As will be addressed later, both Catholics and scholars have reasons to revolt. In matters of sacred liturgy, secular reason and faith traditions often prove incompatible.

Vulgate only?

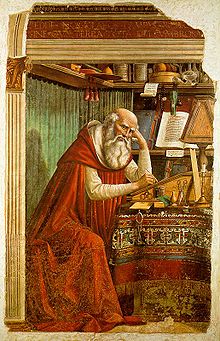

The original Latin Vulgate was so named because it became the ‘vulgar’, the common or the received text of Scripture in the Western Church. Of course one should be careful not to mistake St Hieronymus’s work for the original text of Scripture.

There are additional arguments for this in the history of divine worship. In a liturgical sense, the Vulgate has never functioned as the sole authority.

This is especially visible in the old Divine office and liturgy of the hours. These used to be based on the Greek or ancient Latin, not on Jerome’s Vulgate translation from the Hebrew. The Gallican Psalter (Psalterium Gallicanum) for example, was in use as such for many centuries.

Even after Trent all but canonized Jerome’s translation, the Scriptural passages in the Roman Mass continued to betray dependence on the Vetus Itala rather than on Jerome’s Vulgate. This is evident in the Psalms of the Gradual, but also visible elsewhere. The Gloria settles on the ancient ‘excelsis’ rather than the Vulgate’s ‘altissimus’ or the old Latin alternative ‘alti’. The Pater Noster likewise insists on a Latin version that predates the Vulgate, when it petitions ‘panem nostrum quotidianum da nobis hodie’, rather than ‘panem nostrum supersubstantialem da nobis hodie’.[1] A similar preference is preserved in the Sanctum, which has ‘sanctus sanctus sanctus Dominus Deus Sabaoth’, rather than the Vulgate’s ‘Sanctus, Sanctus, Sanctus Dominus Deus omnipotens’.

These differences indicate that the sacred liturgy continued to prefer established wordings from older Latin translations, also after Jerome’s Vulgate had become the Bible for the Western Church.

My personal experience with Vatican II’s replacement goes back to the first decade after its promulgation by Pope John Paul II in 1979. As a young student in the late 1980’s, I bought a Latin New Testament, supposing that this was the famous translation by St. Hieronymus. It was a text-critical edition, published in 1985 by the Vatican Library and the German Bible Society. Its text was presented as the “New Vulgate”, inviting readers to believe that this was a new version of Jerome’s ancient work. This seemed to be confirmed by its critical apparatus. This did not refer to any Greek, which one would have expected from a new translation into Latin from Greek sources. Instead, it carried textual variants in the extent Vulgate manuscripts. Despite this, there appeared to be no Latin textual witness whatsoever for many of its readings. I found this confusing. Apparently, scholars did not need any manuscript evidence to decide what the Latin text should look like. If required, they just made up their own translation and called this Nova Vulgata.

This was not only ‘because they could’, but unfortunately also because they were specifically instructed to do so by the Vatican. Particularly for the New Testament, the Nova Vulgata adopted textual criticism as the one and supreme norm. John Paul II indicated so much in 1979. In its preface, only accessible to scholars of Latin, he admitted that the Vulgate’s text was ‘prudently improved upon’, whenever critical scholarship did not agree with the Latin manuscripts. For John Paul this was all due to the demands of the times and the legitimate suppositions of critical scholarship.

In his defence, it should be remembered that John Paul II was confronted with this project as a ‘fait accompli’. He was only a few months into his papacy when it was promulgated. John Paul II tended to respect delegated authority and the curia probably told him to sign on the dotted line.

It is perhaps not a coincidence that it was the pope who abolished the anti-modernist oath, Paul VI, who was the one ultimately responsible for this new Bible. Initially, the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) only gave a mandate for a revision of the Latin Psalter. This was bad enough from a liturgical perspective, as this showed that the Vatican was set on discontinuity for the Gradual and the Liturgy of the Hours. Worse was to come, however, because in 1965, Pope Paul VI established a commission to expand the revision to cover the entire Latin Bible, whilst at the same time paying lip-service to Jerome’s Vulgate (cf. Dei Verbum 22, 18th November 1965).[2]

What the anti-modernist oath expressly rejected, adopting textual criticism as the one and supreme norm[3], was now applied as the new standard.

Gatekeepers of the faith

Particularly the text of the New Testament was altered by Pope Paul’s project. If the amount of verses that were changed is any indication, the Protestant King James Bible is much closer to Jerome’s Vulgate than the Vatican’s Nova Vulgata.

The underlying compilation of Greek texts, on which not only the Nova Vulgata but most modern Bible translations are based, does not have any known history in worship, at least not before the 20th century. It was only then that critical scholarship prevailed and put forward a reconstruction of an imaginary ‘original’ text of Scripture that the Church should aspire to. With the assistance of the international Protestant and Catholic Bible societies this reconstruction rapidly replaced the Greek and Latin manuscript traditions that had prevailed since the rise of orthodoxy in the fourth century.

The reconstruction underlying the Nova Vulgata was largely based on a handful of manuscripts. Or more correctly, it was reliant on committee votes. A select group of gatekeepers made determinations on the restoration of what they deemed likely to have been the sacred text.[4] This has proved very much a work in progress, with each new generation of gatekeepers coming up with its determinations and evaluations of manuscripts. The Nestle-Aland text, on which the Nova Vulgata is based, presently travels at version 28. In the meantime, other organisations like the Society of Biblical Literature have produced rival versions.

It should be noted that the two most important of the manuscripts that underlie the Nova Vulgata, codex Vaticanus and Sinaiticus, have no proven history of use in the Church. Sinaiticus even advocates a heretical view on the canon of the New Testament. The fact that Vaticanus survived at all and its extremely corrected state seems to indicate that it never had an intensive history of copying for Church purposes. The two manuscripts disagree amongst themselves in thousands of places. Already in the 19th century it was pointed out that in the Gospels alone Vaticanus is found to omit at least 2877 words; to add 536; to substitute 935; to transpose 2098; to modify 1132 (the corresponding figures for Sinaiticus being 3455, 839, 1114, 2299, 1265 respectively).

Even if one sets these considerations aside, why should a religious community be forced to reject a sacred text that it has cherished for at least 1500 years? Wasn’t the Vulgate an authoritative vehicle for faith in Western Catholicism longer than even liberal scholars care to remember? Generally, most theologians readily agree that sacred texts may grow, be redacted over centuries and be better suited to serve the community of faith as a result. Most contemporary scholars would even insist that many books contained in the Old and New Testament are products of such community-redaction histories. Even when one adopts this post-Enlightenment view of Scripture, what in the world gives a group of scholars, or clerics for that matter, the right to tell a faith community of a billion people to dispense with their ancient tradition for a sacred text?

Even from a modernist point of view this does not make sense at all, unless one desires to actively interfere in sacred traditions and influence the way other people worship and understand the ‘Word of God’.

Scholars’ revolt against JP2

Whereas critical scholarship applauded the radical way in which the Nova Vulgata set aside both Eastern and Western tradition for the New Testament, it condemned its approach for the Old Testament. This was probably due to the fact that the foundational text of most of the Old Testament is a critical edition that was completed by the monks of the Benedictine Abbey of St. Jerome under Pope St. Pius X. In other words: far too conservative and respectful towards Sacred Scripture than desirable in today’s terms. Pope Pius and his Benedictines also wanted to come up with a better Latin version for the Old Testament, but, by and large, their enterprise considered itself accountable to existing Latin manuscripts. Their work was more a revised Vulgate than a new translation. For instance, unsurprisingly (in the light of Hieronymus’s rejection of the Deuterocanonical books) they used the Vetus Latina (collection of Latin Bible translations which predate the Vulgate) as foundational text for the books of Tobit and Judith.

As a result critical scholarship hasn’t been particularly enthusiastic about the Nova Vulgata either. When, in 2001, Pope John Paul II dared to promote the Nova Vulgata as model for all Scripture translation (Liturgiam Authenticam, 2.1.24, May 7, 2001), a revolt of Old Testament scholarship was the result.

In an attempt to safeguard at least a breathing space for traditional Catholicism within the post Vatican II Church, particularly for a young generation of committed Catholics, Pope Benedict followed up with his apostolic letter Summorum Pontificum (7th July 2007), on the use of the Roman liturgy prior to the reform of 1970. Whilst Benedict carefully avoids the words ‘nova’ and ‘vulgata’, he allows a pastor, using his own discretion without additional permissions from a bishop, to celebrate traditional forms of the Latin Mass, setting forth the adapted 1962 version as norm. Pope Benedict’s legislation re-instituted the validity of the ancient Latin rite and safeguarded it against bishops who would otherwise be inclined to actively suppress this.

This legislation had been carefully obstructed both from inside and outside the Vatican, but Benedict made the decision to go ahead with it anyway. ‘For such a celebration with either Missal, the priest needs no permission from the Apostolic See or from his own Ordinary.’ It wasn’t a good way to make friends in high places, as Benedict estranged himself from powerful bishops who had tried to expunge any form of Latin Rite. On the other hand, thousands of young families who care for genuine spirituality and a connection with an unchanging faith of the Church of all Ages are grateful for his decision.

Benedict’s legislation considered ‘the Roman Missal promulgated by Saint Pius V and revised by Blessed John XXIII’ as an ‘extraordinary expression of the same lex orandi of the Church and duly honoured for its venerable and ancient usage’. As this form of mass included readings and recitations from the Vulgate and the Vetus Itala, both Jerome and his predecessors would be considered legitimate in this context.

The reference to Pius V touches on the fact that even without Benedict’s decision exceptional forms of liturgy continued to be permitted for all sorts of orders and monastic associations. These are generally covered by the 1570 papal bull Quo primum. This included, amongst other, an ancient Visigothic Rite from the days of Charlemagne. Otherwise it also applies to Monastic associations that follow the proper missal of the Dominican or Carmelite Rite. These communities do not celebrate the Tridentine Mass, but older liturgies.

Reasons to reject

In summary, Catholics have three good reasons for not using the Nova Vulgata in worship: for what it presents; for what it replaces; and for what it destroys.

1) For what it presents: an imaginary text of Scripture on the authority of scholarship, based on a handful of manuscripts that run contrary to the textual traditions of both the Eastern and the Western Church.

2) For what it replaces: Scriptures with a proven history of common worship of over 1500 years at least. Apart from the legitimate consideration that knowledge of Greek and Latin was much better in the early Church than it is today, and that the Jewish scholars responsible for the Septuagint knew both their Hebrew and Greek better than anyone alive today, people like St Jerome had manuscripts available that were highly regarded at the time, but no longer exist today, like Origen’s Hexapla, which formed the basis for the traditional Latin Psalter of the Church.

3) For what it destroys: the Communion of Saints and our shared patrimonium of worship. For the known history of the Church Christians have used both the Latin and the Byzantine Scriptures to hear the voice of God and to sing his praises with the sacred words of the Psalter. Even from a psychological point of view, it would be a crime to break the vessels that carried the archetypes of Christian civilisation.

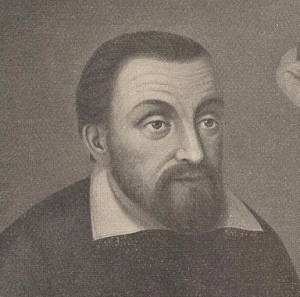

Perhaps, one day, like Bartholomäus Holzhauser anticipated, a great Ecumenical Council will take place and restore the true sense of Scripture.