Man vs God in the Liturgy

The Liturgical Movement, chiefly under Jungmann’s influence, had turned

the liturgy into a battleground of rivalry between God and man as to who

should have the greater glory. The winner of this tug-of-war was

revealed in 1969 with the introduction of the Novus Ordo Mass.

This new rite of Mass was an entirely man-made artefact whose designers

wanted to exalt human values (“active participation,” self-expression,

“work of human hands,” gift offerings from the people etc.) at the

expense of the divine (Christ’s Sacrifice, the forgiveness of sins, the

Real Presence).

This reveals two noteworthy aspects of the reformers who produced the New Mass. They did not take to heart the words of St. John the Baptist: “He [Christ] must increase and I must decrease.” (Jn 3:30) And they displayed a fundamental distaste, even revulsion, for the sacred, authoritative nature of liturgical tradition.

The ensuing revolution in the liturgy has, as would be expected, produced noticeable effects in secularizing the Catholic Church. It has accomplished this by overturning the internal order of the souls of those whose spirituality had been formed in the traditional rites, making them lose the sense of the supernatural that their forebears in the Faith made every effort to encourage.

The evidence for this is all around us that it is the people, not God, who are the center of the liturgy. It is an incontrovertible fact that, generally speaking, modern Catholics routinely talk and laugh aloud in church; they no longer genuflect before the tabernacle, and the habit of visiting the church to pray before the Blessed Sacrament has fallen into demise. In fact, they ignore Jesus present in the tabernacle, preferring to greet each other instead. They have no inhibitions about handling sacred vessels, even consecrated Hosts, or parading themselves in the sanctuary during Mass, and are comfortable with casual and immodest dress in church. All this and much more came about not at the instigation of the laity, but with the connivance and encouragement of the clergy.

Sowing cockle among the wheat

“An enemy hath done this”, we are told, “while men were asleep” (Mat 13: 24-30). It was only when “the blade had grown up and had borne fruit” in the Novus Ordo that it became clear that the traditional Faith had been over-sown by a “new understanding” of the Mass. The unique honor due to God had been virtually written out of the script, and His place usurped by man, who was to be the centre of attention and whose participation was considered essential to the rites.

Who sowed this anthropomorphic cockle among the wheat in the field of the liturgy? Although he had many helpers, and was certainly not the first to do so, Jungmann, by the sheer volume of his writings, should go down in history as the main disseminator of the man-centered liturgy stripped of mystery, awe and reverence.

Down with the ‘allegorical’ traditional liturgy

Jungmann’s role in this desacralization process is of the greatest significance. In his highly influential work on the history of the Mass, and under cover of historical research, he devoted a whole section to the vilification of the medieval liturgy, which he presented as corrupt and decadent. His real purpose seems not to have been to give an accurate account of the historical data according to the standard of Catholic truth, but to smuggle in his own preconceived ideas – which many liturgists simply adopted without argument.

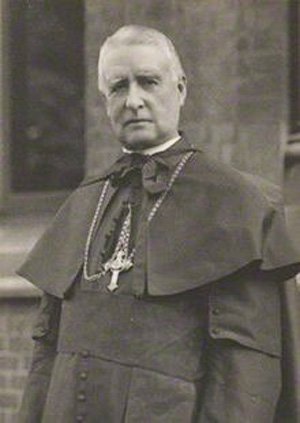

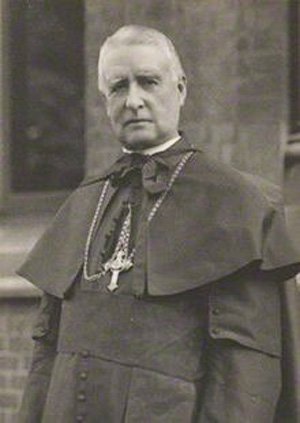

Card. Francis Gasquet in 1916

Jungmann’s main target was the so-called “allegorical method” of

liturgical interpretation, (1) which had been practiced from the

beginning of the Church, passed on by the Church Fathers, the Saints and

Doctors, and still continues to live today among those who are faithful

to Catholic Tradition. Simply put, it was not just a means of

explaining what was going on in the liturgy. It was a hermeneutical tool

of discernment helping pre-Vatican II Catholics to grasp something of

the inner spiritual meaning of the liturgy as inspired by the Holy

Ghost. It served as a reminder that the ceremonies and rites were imbued

with a sacred character – so sacred, in fact, as to become sacrosanct

through consecrated usage. As Dom Francis Gasquet (later Cardinal)

expressed it in the 19th century:

“A Catholic, who sees in the living liturgy of the Roman Church the essential forms which remain still what they were 1,200, perhaps nearly 1,400, years ago, cannot but feel a personal love for those sacred rites which come to him with all the authority of centuries. Any rude handling of such forms must cause deep pain to those who know and use them. For they come to them from God, through Christ and through the Church. But they would not have such attraction were they not also sanctified by the piety of so many generations, who have prayed in the same words and found in them steadiness in joy and consolation in sorrow.” (2) See here

But, nothing in the traditional liturgy, not even the sacred Canon, was sacrosanct to Jungmann and the leaders of the Liturgical Movement. Far from finding it attractive, they not only subjected it to “rude [i.e. rough, insensitive] handling” by violating its dignity, but scorned the piety of the faithful who assisted at it with the greatest devotion throughout the centuries.

As for the “allegorical” tradition of interpreting the liturgy that had served the Church so well since its beginning, Jungmann torpedoed it below the waterline by subtly subjecting the liturgy to the “historical-critical” method of analysis. This method had arisen during the era of the “Enlightenment” which was generally hostile toward the Church, (3) and also from Protestant biblical exegesis. In so doing, he and his colleagues broke the hermeneutical continuity of the liturgy and isolated themselves from the Church’s past. For the “allegorical” interpretation provides an epistemological bridge between ancient and modern times enabling all generations of Catholics to understand the Mass in the same sense.

How the ‘allegorical’ method worked

It has always been acknowledged that the external features – that is to say, the words, actions, chants, architecture and appurtenances – of Catholic worship were instituted to promote the glory of God and the edification of the faithful. The Council of Trent said that the “visible signs of religion and piety” instituted by the Church raise the minds of the faithful “to the contemplation of those most sublime things that are hidden in this Sacrifice.” (4)

But, because we are dealing with mysteries beyond the grasp of the human intellect, we need allegories to help us understand something of the divine truths contained in the liturgy. With reference to the ceremonies of worship, St Thomas Aquinas explained: “the things of God cannot be manifested to men except by means of sensible similitudes. Now these similitudes move the soul more when they are not only expressed in words, but also offered to the senses.” (5)

In other words, in the traditional liturgy, there is nothing merely exterior. Every detail of the ceremonies and decor is expressive of both higher, supernatural realities and the inner, spiritual life so as to direct the minds of the faithful to what is invisible, divine and eternal.

As Fr. Nicholas Gihr, a traditional historian of the Mass, put it:

“The Church has enveloped the celebration of the adorable Sacrifice in a mystic veil, in order to fill the hearts and minds of the faithful with religious awe and profound reverence, and to urge them to earnest, pious contemplation and meditation.” (6)

It was this “mystic veil” that Jungmann (and before him leaders of the Protestant Reformation) (7) wanted to tear away as nothing more than a mythical smokescreen obscuring a more mundane reality that, in the opinion of some, could only be uncovered by historical investigation. Once applied to the whole area of the liturgy, this method of historical criticism permeates everything sacred, displaces the previous method of interpretation and finally changes the perception of the Faith.

In the next article we will give examples of the bad fruits of the “historical-critical” method as they manifested themselves in the reformed liturgy of Paul VI.

To be continued...

Related:

http://tradcatknight.blogspot.com/2015/05/a-reformed-liturgy-turned-against.html

http://tradcatknight.blogspot.com/2014/08/how-bugnini-grew-up-under-pius-xii.html

http://tradcatknight.blogspot.com/2016/02/liturgical-inversion-people-first-god.html

This reveals two noteworthy aspects of the reformers who produced the New Mass. They did not take to heart the words of St. John the Baptist: “He [Christ] must increase and I must decrease.” (Jn 3:30) And they displayed a fundamental distaste, even revulsion, for the sacred, authoritative nature of liturgical tradition.

The ensuing revolution in the liturgy has, as would be expected, produced noticeable effects in secularizing the Catholic Church. It has accomplished this by overturning the internal order of the souls of those whose spirituality had been formed in the traditional rites, making them lose the sense of the supernatural that their forebears in the Faith made every effort to encourage.

The evidence for this is all around us that it is the people, not God, who are the center of the liturgy. It is an incontrovertible fact that, generally speaking, modern Catholics routinely talk and laugh aloud in church; they no longer genuflect before the tabernacle, and the habit of visiting the church to pray before the Blessed Sacrament has fallen into demise. In fact, they ignore Jesus present in the tabernacle, preferring to greet each other instead. They have no inhibitions about handling sacred vessels, even consecrated Hosts, or parading themselves in the sanctuary during Mass, and are comfortable with casual and immodest dress in church. All this and much more came about not at the instigation of the laity, but with the connivance and encouragement of the clergy.

Sowing cockle among the wheat

“An enemy hath done this”, we are told, “while men were asleep” (Mat 13: 24-30). It was only when “the blade had grown up and had borne fruit” in the Novus Ordo that it became clear that the traditional Faith had been over-sown by a “new understanding” of the Mass. The unique honor due to God had been virtually written out of the script, and His place usurped by man, who was to be the centre of attention and whose participation was considered essential to the rites.

Who sowed this anthropomorphic cockle among the wheat in the field of the liturgy? Although he had many helpers, and was certainly not the first to do so, Jungmann, by the sheer volume of his writings, should go down in history as the main disseminator of the man-centered liturgy stripped of mystery, awe and reverence.

Down with the ‘allegorical’ traditional liturgy

Jungmann’s role in this desacralization process is of the greatest significance. In his highly influential work on the history of the Mass, and under cover of historical research, he devoted a whole section to the vilification of the medieval liturgy, which he presented as corrupt and decadent. His real purpose seems not to have been to give an accurate account of the historical data according to the standard of Catholic truth, but to smuggle in his own preconceived ideas – which many liturgists simply adopted without argument.

Card. Francis Gasquet in 1916

“A Catholic, who sees in the living liturgy of the Roman Church the essential forms which remain still what they were 1,200, perhaps nearly 1,400, years ago, cannot but feel a personal love for those sacred rites which come to him with all the authority of centuries. Any rude handling of such forms must cause deep pain to those who know and use them. For they come to them from God, through Christ and through the Church. But they would not have such attraction were they not also sanctified by the piety of so many generations, who have prayed in the same words and found in them steadiness in joy and consolation in sorrow.” (2) See here

But, nothing in the traditional liturgy, not even the sacred Canon, was sacrosanct to Jungmann and the leaders of the Liturgical Movement. Far from finding it attractive, they not only subjected it to “rude [i.e. rough, insensitive] handling” by violating its dignity, but scorned the piety of the faithful who assisted at it with the greatest devotion throughout the centuries.

As for the “allegorical” tradition of interpreting the liturgy that had served the Church so well since its beginning, Jungmann torpedoed it below the waterline by subtly subjecting the liturgy to the “historical-critical” method of analysis. This method had arisen during the era of the “Enlightenment” which was generally hostile toward the Church, (3) and also from Protestant biblical exegesis. In so doing, he and his colleagues broke the hermeneutical continuity of the liturgy and isolated themselves from the Church’s past. For the “allegorical” interpretation provides an epistemological bridge between ancient and modern times enabling all generations of Catholics to understand the Mass in the same sense.

How the ‘allegorical’ method worked

It has always been acknowledged that the external features – that is to say, the words, actions, chants, architecture and appurtenances – of Catholic worship were instituted to promote the glory of God and the edification of the faithful. The Council of Trent said that the “visible signs of religion and piety” instituted by the Church raise the minds of the faithful “to the contemplation of those most sublime things that are hidden in this Sacrifice.” (4)

But, because we are dealing with mysteries beyond the grasp of the human intellect, we need allegories to help us understand something of the divine truths contained in the liturgy. With reference to the ceremonies of worship, St Thomas Aquinas explained: “the things of God cannot be manifested to men except by means of sensible similitudes. Now these similitudes move the soul more when they are not only expressed in words, but also offered to the senses.” (5)

In other words, in the traditional liturgy, there is nothing merely exterior. Every detail of the ceremonies and decor is expressive of both higher, supernatural realities and the inner, spiritual life so as to direct the minds of the faithful to what is invisible, divine and eternal.

As Fr. Nicholas Gihr, a traditional historian of the Mass, put it:

“The Church has enveloped the celebration of the adorable Sacrifice in a mystic veil, in order to fill the hearts and minds of the faithful with religious awe and profound reverence, and to urge them to earnest, pious contemplation and meditation.” (6)

It was this “mystic veil” that Jungmann (and before him leaders of the Protestant Reformation) (7) wanted to tear away as nothing more than a mythical smokescreen obscuring a more mundane reality that, in the opinion of some, could only be uncovered by historical investigation. Once applied to the whole area of the liturgy, this method of historical criticism permeates everything sacred, displaces the previous method of interpretation and finally changes the perception of the Faith.

In the next article we will give examples of the bad fruits of the “historical-critical” method as they manifested themselves in the reformed liturgy of Paul VI.

To be continued...

Related:

http://tradcatknight.blogspot.com/2015/05/a-reformed-liturgy-turned-against.html

http://tradcatknight.blogspot.com/2014/08/how-bugnini-grew-up-under-pius-xii.html

http://tradcatknight.blogspot.com/2016/02/liturgical-inversion-people-first-god.html

- It might be helpful to know that the word “allegory” is derived from a combination of two Greek words: agoreuo: to say/speak publicly in the agora – a gathering place or assembly – and allos: other. The term came to denote how we can explain the “other” i.e. the higher or mystical meaning of a text or ceremony that is not immediately evident to the eye or ear.

- Francis Gasquet and Edmund Bishop, Edward VI and the Book of Common Prayer, London: John Hodles, 1890, p. 183. Having served as Prior of Downside Abbey, Gasquet was elected Abbot President of the English Benedictines in 1900 and was made a Cardinal in 1914. As a member of the Pontifical Commission to study the validity of the Anglican ordinations (1896), he made a major contribution to the drafting of Leo XIII’s Bull Apostolicae Curae, on the invalidity of Anglican orders.

- It was in this period that the Synod of Pistoia was held, which, significantly, proposed many liturgical reforms that prefigure those of Vatican II.

- Session 22, Chapter 5.

- Summa Theologica, II. I, q. 99 a. 3.

- Fr Nicholas Gihr, The Holy Sacrifice Dogmatically, Liturgically and Ascetically Explained, Freiburg: Herder, 1902, p. 336.

- Allegorical interpretation of the Bible and the liturgy came under sustained attack during the 16th century from both Humanists and Protestants. Their fundamental objection was the authority of the Catholic Church in the area of exegesis.